THE ARAB CONQUEST (637 AD)

The first conflict between local

Bedouin tribes and Sasanian forces seems to have been in 634, when the

Arabs were defeated at the Battle of the Bridge. There a

force of some 5,000 Muslims under Abu 'Ubayd ath-Thaqafi

was routed by the Persians. In 637 a much larger Muslim force under

Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas defeated the main Persian army at the

battle of Al-Qadisiyya and moved on to sack

Ctesiphon. By the end of the following year (638), the Muslims

had conquered almost all of Iraq, and the last Sasanian king,

Yazdegerd III, had fled to Iran, where he was killed in 651.

The Muslim conquest was followed by mass immigration of Arabs from

eastern Arabia and Oman. These new arrivals did not disperse and settle

throughout the country; instead they established two new garrison cities,

at Al-Kufah, near ancient Babylon, and at Basra

in the south. The intention was that the Muslims should be a separate

community of fighting men and their families living off taxes paid by the

local inhabitants. In the north of the country, Mosul

began to emerge as the most important city and the base of a Muslim

governor and garrison. Apart from the Persian elite and the Zoroastrian

priests, whose property was confiscated, most of the local people were

allowed to keep their possessions and their religion.

Iraq now became a province of the Muslim Caliphate, which stretched

from North Africa and later Spain in the

west to Sind (now southern Pakistan) in the east. At

first the capital of the Caliphate was at Madinah

(Medina), but, after the murder of the third caliph, 'Uthman,

in 656, his successor, the Prophet's cousin and son-in-law

Ali, made Iraq his base. In 661, however, 'Ali was

murdered in Al-Kufah, and the caliphate passed to the rival

Umayyad family in Syria. Iraq became a subordinate province, even

though it was the richest area of the Muslim world and the one with the

largest Muslim population. This situation gave rise to continual

discontent with Umayyad rule; this discontent was in various forms.

In 680 'Ali's son

al-Husayn arrived in Iraq from Madinah, hoping that

the people of Al-Kufah would support him. They failed to act, and his

small group of followers was massacred at

Karbala', but his memory lingered on as a source of

inspiration for all who opposed the Umayyads. In later centuries, Karbala'

and 'Ali's tomb at nearby An-Najaf became important centres of

Shi'ite pilgrimage and are still greatly revered today. The

Iraqis had their opportunity after the death in 683 of the caliph

Yazid I when the Umayyads faced threats from many quarters. In

Al-Kufah the initiative was taken by al-Mukhtar ibn Abi 'Ubayd,

who was supported by many "mawali", non-Arab converts to

Islam who felt they were treated as second-class citizens. Al-Mukhtar was

killed in 687, but the Umayyads realized that strict rule was required.

The caliph 'Abd al-Malik (685-705) appointed the fearsome

al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf as his governor in Iraq and all of

the east. Al-Hajjaj became a legend as a stern but just ruler. His firm

measures aroused the opposition of the local Arab elite, and in 701 there

was a massive rebellion led by Muhammad ibn al-Ash'ath.

The insurrection was defeated only with the aid of Syrian soldiers. Iraq

was now very much a conquered province, and al-Hajjaj established a new

city at Wasit, halfway between Al-Kufah and Basra, to be

a base for a permanent Syrian garrison. In a more positive way, he

encouraged Iraqis to join the expeditions led by Qutaybah ibn

Muslim that between 705 and 715 conquered what is now Central

Asia for Islam. Even after al-Hajjaj's death in 714, the Umayyad-Syrian

grip on Iraq remained firm, and resentment was widespread.

In 680 'Ali's son

al-Husayn arrived in Iraq from Madinah, hoping that

the people of Al-Kufah would support him. They failed to act, and his

small group of followers was massacred at

Karbala', but his memory lingered on as a source of

inspiration for all who opposed the Umayyads. In later centuries, Karbala'

and 'Ali's tomb at nearby An-Najaf became important centres of

Shi'ite pilgrimage and are still greatly revered today. The

Iraqis had their opportunity after the death in 683 of the caliph

Yazid I when the Umayyads faced threats from many quarters. In

Al-Kufah the initiative was taken by al-Mukhtar ibn Abi 'Ubayd,

who was supported by many "mawali", non-Arab converts to

Islam who felt they were treated as second-class citizens. Al-Mukhtar was

killed in 687, but the Umayyads realized that strict rule was required.

The caliph 'Abd al-Malik (685-705) appointed the fearsome

al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf as his governor in Iraq and all of

the east. Al-Hajjaj became a legend as a stern but just ruler. His firm

measures aroused the opposition of the local Arab elite, and in 701 there

was a massive rebellion led by Muhammad ibn al-Ash'ath.

The insurrection was defeated only with the aid of Syrian soldiers. Iraq

was now very much a conquered province, and al-Hajjaj established a new

city at Wasit, halfway between Al-Kufah and Basra, to be

a base for a permanent Syrian garrison. In a more positive way, he

encouraged Iraqis to join the expeditions led by Qutaybah ibn

Muslim that between 705 and 715 conquered what is now Central

Asia for Islam. Even after al-Hajjaj's death in 714, the Umayyad-Syrian

grip on Iraq remained firm, and resentment was widespread.

The 'Abbasid caliphate

Opposition to the Umayyads

finally came to a head in northeastern Iran (Khorasan) in 747 when the

mawla Abu Muslim raised black banners in the name of the

'Abbasids, a branch of the family of the Prophet,

distantly related to 'Ali and his descendants. In 749 the armies from the

east reached Iraq, where they received the support of much of the

population. The 'Abbasids themselves came from their retreat at

Humaymah in southern Jordan, and in 749 the first 'Abbasid

caliph, as-Saffah, was proclaimed in the mosque at

Al-Kufah.

This " 'Abbasid Revolution" ushered in the

golden age of medieval Iraq. Khorasan was too much on the

fringes of the Muslim world to be a suitable capital, and from the

beginning the 'Abbasid caliphs made Iraq their base. By this time Islam

had spread well beyond the original garrison towns, even though Muslims

were still a minority of the population.

At first the 'Abbasids ruled from

Al-Kufah or nearby, but in 762 al-Mansur founded

a new capital on the site of the old village of Baghdad.

It was officially known as

Madinat as-Salam

("City of Peace"), but in popular usage the old name prevailed. Baghdad

soon became larger than any city in Europe or western Asia. Al-Mansur

built the massive Round City with four gates and his palace and the main

mosque in the centre. This Round City was exclusively a government

quarter, and soon after its construction the markets were banished to the

Karkh suburb to the south. Other suburbs soon grew up,

developed by leading courtiers: Harbiyyah to the

northeast, where the Khorasani soldiers were settled, and, across the

Tigris on the east bank, a new palace quarter for the caliph's son and

heir al-Mahdi.

The sitting of Baghdad

proved to be an act of genius. It had access to both the Tigris

and Euphrates river systems and was close to the main

route through the Zagros Mountains to the Iranian

plateau. Wheat and barley from Al-Jazirah and

dates and rice from Basra and the south could be brought

by water. By the year 800 the city may have had as many as 500,000

inhabitants and was an important commercial centre as well as the seat of

government. The city grew at the expense of other centers, and both the

old Sasanian capital at Ctesiphon (called Al-Mada'in,

"The Cities," by the Arabs) and the early Islamic centre at Al-Kufah

fell into decline.

The high point of prosperity was probably

reached in the reign of Harun ar-Rashid (786-809), when

Iraq was very much the centre of the empire and riches flowed into the

capital from all over the Muslim world. The prosperity and order in the

southern part of the country was, however, offset by outbreaks of

lawlessness in Al-Jazirah, notably the rebellion of the

Bedouin Walid ibn Tarif, who defied government forces

between 794 and 797. Even the most powerful governments found it difficult

to extend their authority beyond the limits of the settled land.

Much more serious disruption followed the

death of Harun in 809. He left his son al-Amin as caliph

in Baghdad but divided the Caliphate and gave his son al-Ma'mun

control over Iran and the eastern half of the empire. This arrangement

soon broke down, and there ensued a prolonged and very destructive civil

war. The supporters of al-Amin made an ill-judged attempt to invade Iran

in the spring of 811 but were soundly defeated at Rayy

(modern Shahr-e Rey, just south of modern Tehran). Al-Ma'mun's supporters

retaliated by invading Iraq, and from August 812 until September 813 they

laid siege to Baghdad, while the rest of Iraq slid into anarchy. The

collapse of Baghdadi resistance and the death of al-Amin did not improve

matters, for al-Ma'mun, now generally recognized as caliph, decided to

rule from Marw in distant Khorasan

(modern Mary, in Turkmenistan).This downgrading of Iraq united many

different groups in prolonged and bitter resistance to al-Ma'mun's

governor and led to another siege of Baghdad. Finally al-Ma'mun was forced

to concede that he could not rule from a distance, and in August 819 he

returned to Baghdad.

Once again Iraq was the central province of

the Caliphate and Baghdad the capital, but the prolonged conflict had left

much of Baghdad in ruins and caused great destruction in the countryside.

It probably marked the beginning of the long decline in the prosperity of

the area; this decline was marked from the 9th century onward. Al-Ma'mun

sent his generals to bring Syria and Egypt

back under 'Abbasid rule and set about restoring the government apparatus,

many of the administrative records having been destroyed in the fighting.

His reign in Baghdad (819-833) saw Iraq become the centre of remarkable

cultural activity, notably the translation of Greek science and philosophy

into Arabic. The caliph himself collected texts, employed translators like

the celebrated Hunayn ibn Ishaq, and established an

academy in Baghdad, the Bayt al-Hikmah ("House of

Wisdom"), with a library and an observatory. Private patrons such as the

Banu Musa brothers followed his example. This activity

had a profound effect not only on Muslim intellectual life but also on the

intellectual life of western Europe, for much of the science and

philosophy taught in universities in the Middle Ages was derived from

these Arabic translations, rendered into Latin in Spain

in the 12th century.

Politically the position was less rosy. Al-Ma'mun

was unable to recruit sufficient forces to replace the old 'Abbasid army

that had been destroyed in the civil war, and he became increasingly

dependent on his younger brother, Abu Ishaq, who had

gathered a small but highly efficient force of Turkish mercenaries,

many of them slaves or ex-slaves from Central Asia. When al-Ma'mun died in

833, Abu Ishaq, under the title of al-Mu'tasim, succeeded

him without difficulty. Al-Mu'tasim was no intellectual but rather an

effective soldier and administrator. His reign marks the introduction into

Iraq of an alien, usually Turkish, military class, which was to dominate

the political life of the country for centuries to come. From this time

Iraqi Arabs were rarely employed in military positions, though they

continued to be influential in the civil administration.

The recruitment of this new military class

provoked resentment among the Baghdadis, who felt that they were being

excluded from power. This resentment led al-Mu'tasim to found a new

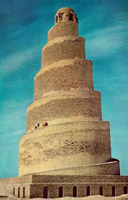

capital at Samarra', the last major urban foundation in

Iraq until the 20th century. He chose a site on the Tigris about 100 miles

north of Baghdad. Here he laid out a city with palaces and mosques, broad

straight streets, and a regular pattern of housing. The ruins of this

city, which was expanded by his successor al-Mutawwakil

(847-861), can still be seen on the ground and, more strikingly, in aerial

photographs, in which the whole plan can be made out. Samarra' became a

vast city, but it had none of the natural advantages of Baghdad:

communication by river and canal with the Euphrates and southern Iraq was

much more difficult, and despite massive investment the water supply was

always inadequate. Samarra' survived only while it was the capital of the

Caliphate, from 836 to 892. When the caliphs returned to Baghdad, it

showed no independent urban vitality and soon shrank to a small provincial

town, which is why its remains can still be seen when all traces of early

'Abbasid Baghdad have disappeared.

For nearly 30 years the new regime worked

well, and Iraq was for the last time the centre of a large empire. Tax

revenues from other areas enriched Samarra', and Baghdad continued to

prosper under the rule of the Tahirid family. Basra

remained a great entrepÔt on the Persian Gulf. The employment of Turkish

soldiers without any ties to the local community gave rise to political

instability, however. In 861 the caliph al-Mutawwakil was

assassinated in his palace in Samarra' by disaffected troops, and there

began a nine-year anarchy in which the Turkish soldiers made and deposed

caliphs virtually at will. In 865 open civil war raged between Samarra'

and Baghdad, resulting in another destructive siege of Baghdad. The

anarchy played itself out, and in 870 stability was restored with the

caliph al-Mu'tamid in Samarra' as titular ruler and his

dynamic military brother al-Muwaffaq exercising real

power in Baghdad, but the anarchy had done real and lasting damage to

Iraq. Almost all the provinces of the empire, both the Iranian

lands in the east and Syria and Egypt to

the west, had broken away and become independent. Worse, a major social

revolt had broken out in southern Iraq itself. In the prosperous years of

early Islamic Iraq, large numbers of slaves had been imported from East

Africa to be used in grueling agricultural work in the marshes of southern

Iraq. In 869 they rose in rebellion, led by an Arab who claimed to be a

descendant of 'Ali. This rebellion was extremely serious for the 'Abbasid

government: it laid to waste large areas of agricultural land, and the

great trading port of Basra was taken and sacked in 871, the rebels

burning mosques and houses and massacring the inhabitants with

indiscriminate ferocity. Although Basra was soon recaptured, it is

unlikely that it ever fully recovered, and trade shifted down the gulf to

cities such as Siraf (modern Taheri) in southern Iran.

The crushing of this revolt involved long and hard amphibious campaigns in

the marshes, led by al-Muwaffaq and his son Abu'

l-'Abbas (later the caliph al-Mu'tathid) from

879 until the rebel stronghold at Mukhtarah was finally

taken in 883.

For nearly 30 years the new regime worked

well, and Iraq was for the last time the centre of a large empire. Tax

revenues from other areas enriched Samarra', and Baghdad continued to

prosper under the rule of the Tahirid family. Basra

remained a great entrepÔt on the Persian Gulf. The employment of Turkish

soldiers without any ties to the local community gave rise to political

instability, however. In 861 the caliph al-Mutawwakil was

assassinated in his palace in Samarra' by disaffected troops, and there

began a nine-year anarchy in which the Turkish soldiers made and deposed

caliphs virtually at will. In 865 open civil war raged between Samarra'

and Baghdad, resulting in another destructive siege of Baghdad. The

anarchy played itself out, and in 870 stability was restored with the

caliph al-Mu'tamid in Samarra' as titular ruler and his

dynamic military brother al-Muwaffaq exercising real

power in Baghdad, but the anarchy had done real and lasting damage to

Iraq. Almost all the provinces of the empire, both the Iranian

lands in the east and Syria and Egypt to

the west, had broken away and become independent. Worse, a major social

revolt had broken out in southern Iraq itself. In the prosperous years of

early Islamic Iraq, large numbers of slaves had been imported from East

Africa to be used in grueling agricultural work in the marshes of southern

Iraq. In 869 they rose in rebellion, led by an Arab who claimed to be a

descendant of 'Ali. This rebellion was extremely serious for the 'Abbasid

government: it laid to waste large areas of agricultural land, and the

great trading port of Basra was taken and sacked in 871, the rebels

burning mosques and houses and massacring the inhabitants with

indiscriminate ferocity. Although Basra was soon recaptured, it is

unlikely that it ever fully recovered, and trade shifted down the gulf to

cities such as Siraf (modern Taheri) in southern Iran.

The crushing of this revolt involved long and hard amphibious campaigns in

the marshes, led by al-Muwaffaq and his son Abu'

l-'Abbas (later the caliph al-Mu'tathid) from

879 until the rebel stronghold at Mukhtarah was finally

taken in 883.

The reigns of al-Mu'tathid

(892-902) and his son al-Muktafi (902-908) saw Iraq

united under 'Abbasid control. Once more Baghdad was the

capital, although the caliphs had largely abandoned the Round City of al-Mansur

on the west bank, and the centre of government now lay on the east bank in

the area that has remained the centre of the city ever since. It was a

period of great cultural activity, and Baghdad was home to many

intellectuals, including the great historian at-Tabari,

whose vast work chronicled the early history of the Muslim state; however,

it was no longer the capital of a great empire. During the reign of the

boy caliph al-Muqtadir (908-932), the political situation

deteriorated rapidly. The weakness of the caliph gave rise to endless

intrigues among parties of viziers and to a growing tendency for the

military to take matters into its own hands. Increasingly the government

in Baghdad lost control of the revenues and lands of Iraq. In 935 the

final crisis occurred when the caliph ar-Rai was obliged

to hand over all real secular power to an ambitious general, Ibn

Ra'iq.

The political catastrophe of the 'Abbasid

Caliphate was accompanied by economic collapse. It is probable that the

vicious circle of decline started with the civil war after Harun's

death in 809, and there can be no doubt that it was exacerbated by the

demands of the Turkish military for payment.

Administrators increasingly resorted to short-term expedients such as tax

farming, which encouraged extortion and oppression, and the granting of

iqtas to the military. In theory, iqta's

were grants of the right to collect and use tax revenues; they could not

be inherited or sold. The purpose of an iqta' was that

the soldiers themselves would collect what they could directly from lands

assigned to them. Both these remedies put a premium on short-term

exploitation of land rather than long-term investment. Except in the

north, most Iraqi agriculture was dependent on investment in and upkeep of

complex irrigation works, and these new fiscal systems proved disastrous.

In 935, the same year in which ar-Rai handed over power

to the military leader Ibn Ra'iq, the greatest of the

ancient irrigation works of central Iraq, the Nahrawan canal,

was breached to impede an advancing army. The damage was never repaired,

large areas went out of cultivation, and villages were abandoned. The

destruction of the canal is symbolic of the end of the irrigation culture

that had brought great wealth to ancient Mesopotamia and

that had underpinned Sasanian and early Islamic government.

Zinj rebellion (869-883 AD)

(ad 869-883), a black-slave revolt against the 'Abbasid caliphal

empire. A number of Basran landowners had brought several thousand East

African blacks (Zinj) into southern Iraq to drain the salt marshes east of

Basra. The landowners subjected the Zanj, who generally

spoke no Arabic, to heavy slave labour and provided them with only minimal

subsistence. In September 869, 'Ali ibn Muhammad, a

Persian claiming descent from 'Ali, the fourth caliph,

and Fatimah, Muhammad's daughter, gained

the support of several slave-work crews--which could number from 500 to

5,000 men--by pointing out the injustice of their social position and

promising them freedom and wealth. 'Ali's offers became even more

attractive with his subsequent adoption of a Kharijite religious stance:

anyone, even a black slave, could be elected caliph, and all non-Kharijites

were infidels threatened by a holy war.

Zanj forces grew rapidly in size and power, absorbing the well-trained

black contingents that defected from the defeated caliphal armies, along

with some disaffected local peasantry. In October 869 they defeated a

Basran force, and soon afterward a Zinj capital, al-Mukhtarah

(Arabic: the Chosen), was built on an inaccessible dry spot in

the salt flats, surrounded by canals. The rebels gained control of

southern Iraq by capturing al-Ubullah (June 870), a

seaport on the Persian Gulf, and cutting communications to Basra, then

seized Ahwaz in southwestern Iran. The caliphal armies,

now entrusted to al-Muwaffaq, a brother of the new

caliph, al-Mu'tamid (reigned 870-892), still could not

cope with the rebels. The Zinj sacked Basra in September

871, and subsequently defeated al-Muwaffaq himself in

April 872.

Between 872 and 879, while al-Muwaffaq was occupied in

eastern Iran with the expansion of the Saffarids, an

independent Persian dynasty, the Zinj seized Wasit (878)

and established themselves in Khuzistan, Iran. In 879,

however, al-Muwaffaq organized a major offensive against

the black slaves. Within a year, the second Zinj city, al-Mani'ah

(The Impregnable), was taken. The rebels were next expelled from

Khuzistan, and, in the spring of 881, al-Muwaffaq

laid siege to al-Mukhtarah from a special city built on

the other side of the Tigris River. Two years later, in August 883,

reinforced by Egyptian troops, al-Muwaffaq finally

crushed the rebellion, conquering the city and returning to Baghdad with

'Ali's head.

The Buyid period (945-1055 AD)

After a decade of chaos, when Ibn Ra'iq and other

military leaders struggled for power, an element of stability was regained

in 945 when Baghdad was taken by the Buyid

chief, Mu'izz ad-Dawlah. The Buyids were leaders of the

Daylamite people from the area southwest of the Caspian

Sea. These hardy mountaineers had taken advantage of the prevailing

anarchy to take over much of western Iran in 934, and they now moved into

Iraq. Mu'izz ad-Dawlah established himself in Baghdad,

but his regime never ruled over all of Iraq. In the capital itself there

was always tension between the Daylamites and the

Turks who had traditionally been the main military force. When

the Buyids made known their adherence to the

Shi'ite branch of Islam, there was further, often violent,

tension between their supporters and the Sunnites, who

were in the majority. Baghdad began to disintegrate into a number of small

communities, each either Sunnite or Shi'ite and each with its own walls to

protect it from its neighbors. Large areas, including much of the Round

City of al-Mansur, fell into ruin. Further problems were

caused by the loss of control of Al-Jazirah in the north

of Iraq, for it was from this area that Baghdad had traditionally received

its grain supplies. The city was too populous to be fed from its own

hinterland, and, when political conflict interrupted the grain supplies

from Al-Jazirah, famine was added to the other miseries

of the people. In one area, however, the Buyids retained

the old forms: rather than make a clean break, they allowed the 'Abbasid

caliphs to remain in comfortable but secluded captivity in their palace in

Baghdad. Those who forgot where real power lay, however, were soon

brutally reminded.

From the beginning of the 10th century, Iraq was usually divided

politically, and the Buyids in Baghdad

seldom controlled the whole area as their 'Abbasid predecessors had done.

The area around Basra in the south was frequently in the

hands of rival Buyid princes, and the north increasingly

went its own way. The economic decline and the ruin of irrigation systems

that had affected central and southern Iraq do not seem to have been as

marked in Al-Jazirah, where agriculture was largely dry

farming, based on rainfall; the area was consequently less potentially

wealthy than the south but also less vulnerable to political upset.

Mosul had been the most important city in Al-Jazirah

since the Islamic conquest, and it now became an important regional

capital. The area was dominated by the Hamdani family.

Originally leaders of the Taghlib Bedouin tribe of

Al-Jazirah, members of this family had taken service in

the 'Abbasid armies. In 935 their leader, Nasir

ad-Dawlah, was acknowledged as ruler of Mosul in

exchange for a money tribute and the provision of grain for

Baghdad and Samarra', though neither money nor

grain was paid on a regular basis. The Hamdanids

strengthened their position by recruiting Turkish

soldiers for their army and by establishing good relations with the

leaders of the Kurdish tribes in the hills to the north.

In 967 Nasir ad-Dawlah was succeeded by his son

Abu Taghlib, but in 977 the greatest of the

Buyids of Iraq, 'Aud ad-Dawlah, took

Mosul and drove the Hamdanids out. This triumph

did not unite Iraq for long; after 'Aud ad-Dawlah died in

983, his more feeble successors allowed northern Iraq to slip from their

hands. Increasingly power in the north was assumed by the sheikhs of the

Banu 'Uqayl, the largest Bedouin tribe in Al-Jazirah.

By the early 11th century the 'Uqaylid leader

Qirwash dominated Mosul and Al-Jazirah.

Unlike the Hamdanids and the Buyids, the

'Uqayli sheikhs lived in desert encampments rather than

in cities, and they relied on their tribesmen rather than on

Turkish or Daylamite soldiers. By 1010

Qirwash's power extended as far south as Al-Kufah,

though Baghdad itself never came under Bedouin control,

and he tried to arrange an alliance with the Fatimid

caliphs of Egypt. From then on his power began to

decline, and in the early 1040s the Banu 'Uqayl found

themselves threatened by a new enemy, the Oguz Turkish

tribes invading from Iran. In 1044, northwest of Mosul,

these Turks and the Bedouin Arabs fought a major battle, in which the

Turks were soundly defeated. Although little reported by historians, it is

probable that this battle ensured that the people of the plains of

northern Iraq remained Arabic-speaking, unlike the inhabitants of the

steppelands of Anatolia to the north, who spoke Turkish.

In the south, too, the Bedouin became increasingly powerful. On the

desert frontier in the Al-Kufah area the Banu

Mazyad, the leading sheikhs of the Asad tribe,

established a small state that reached its apogee during the long reign of

Dubays (1018-1081). During this time their main camp

(Arabic: hillah) became an important town and, under the name Al-Hillah,

replaced early Islamic Al-Kufah as the largest urban

centre in the area.

Baghdad and the surrounding area from the lower Tigris

south to the Persian Gulf remained more or less under Buyid

rule. In 978 Baghdad was taken by the Buyid

ruler of Fars (southwest Iran), 'Aud ad-Dawlah.

In the five years before his death in 983, he made a serious attempt to

rebuild the administration, to control the Bedouin, and to reunite

Mosul with southern Iraq. In addition to being a patron of

learning, he made efforts to restore damaged irrigation systems. Such

determination was unfortunately rare, and after his death his lands were

divided. The later Buyids had great difficulty in

governing even Baghdad and the immediately surrounding

area. Poverty compounded their problems; Jalal ad-Dawlah

(reigned 1025-1044) was obliged to send away his servants and release his

horses because he could no longer afford to feed them.

Baghdad presented a picture of devastation in this

period. Brigands maintained themselves by kidnapping and extortion, and

disputes between the Sunnites and the Shi'ites

became increasingly violent. The Shi'ites, though less numerous, were

sometimes encouraged by Buyid princes who wished to win

their support. This prompted the Sunnites to look to the 'Abbasid caliphs

for leadership. The caliph al-Qadir (991-1031) assumed

the religious leadership of the Sunnites and published a manifesto, the

Risala al-Qadiriyya (1029), in which the main tenets of

Sunnite belief were outlined. He did not, however, attain any significant

political power.

Despite this disorder and political chaos, Baghdad

remained an intellectual centre. The lack of firm political authority

meant that free debate and exchange of ideas could take place in a way

that was not possible under more authoritarian regimes. This anarchic but

culturally productive era in the history of Iraq came to an end in

December 1055 when the Seljuq Turkish leader

Toghrl Beg entered the city with his forces and rapidly

established a secure government over most of Iraq. The country had seen

many changes since the 7th century. Much of the ethnic and religious

diversity of late Sasanian Iraq had disappeared. Apart

from the Turkish military and the Kurds

of the mountainous areas, most people now spoke Arabic.

There were still Christian communities, especially in the

northern areas around Tikrit and Mosul,

but the majority of the population was now Muslim. Within

the Muslim community, however, there were serious divisions between

Sunnites and Shi'ites. Iraq had also lost its position as the richest area

of the Middle East. There are no figures, but it would probably be right

to assume that the population had declined significantly, and it is clear

that many able and enterprising people sought to escape the chaos by

migrating to Egypt. Iraq had lost its imperial role

forever.

The Seljuqs (1055-1152)

The Sunnite Seljuq leader Toghrl Beg

entered Baghdad in December 1055, arresting and

imprisoning the Buyid prince al-Malik ar-Rahim

(1048-55). Without meeting the 'Abbasid caliph, he proceeded against the

'Uqaylids in Mosul, taking the city in

1057 and retaining the 'Uqaylid ruler as governor there

on behalf of the Seljuqs. On his return to

Baghdad in 1058, Toghrl was finally received by

the caliph al-Qa'im (1031-75), who granted him the title

"king of the East and West."

On Dec. 27, 1058, with Toghrl busy elsewhere, the

Buyid slave general Arslan al-Muzaffar al-Basasiri

and the 'Uqaylid ruler Quraysh ibn Badran

(1052-61) occupied Baghdad, recognizing al-Mustansir,

the Shi'ite Fatimid caliph of Egypt and

Syria, and sending him the insignia of rule as trophies.

Al-Basasiri expelled al-Qa'im and, with

the help of the Mazyadid Dubays I (1018-81), quickly

extended his control over Wasit and Basra.

Both the Fatimids and the Mazyadids

withdrew their support, however, and al-Basasiri was

killed by Seljuq forces in 1060. Toghrl

reinstated al-Qa'im as caliph, who then gave him

additional honours, including the title sultan (Arabic:

sultan, "authority"), found on coins minted in the names of both the

caliph and the sultan. The Seljuqs now tried to rid Iraq

of all Shi'ite influences. Exchanging Shi'ite Buyid emirs

for Sunnite Seljuq sultans, while perhaps ideologically

appropriate, made little practical difference for the 'Abbasid caliphs,

who remained captives in the hands of military strongmen. Though

Baghdad continued as the seat of the caliphate, the

Seljuq sultans ultimately established their capital at

Esfahan in Persian Iraq. The relations between caliph and sultan

were formalized by the great theologian al-Ghazali (d.

1111) as follows :-

(( Government in these days is a consequence solely of military

power, and whosoever he may be to whom the holder of military power gives

his allegiance, that person is Caliph. And whosoever exercises independent

authority, so long as he shows allegiance to the Caliph in the matter of

his prerogatives [of sovereignty], the same is a sultan, whose commands

and judgments are valid in the several parts of the earth. ))

These and other politico-religious doctrines were universalized through

the spread of a system of educational institutions (madrasahs), associated

with the powerful Seljuq minister Nizam al-Mulk

(d. 1092), an Iranian from Khorasan. The institutions

were called Nizamiyahs in his honour. The most famous of

them, the Baghdad Nizamiyah, was founded in 1067.

Nizam al-Mulk argued for the creation of a strong central

political authority, focused on the sultan and modeled on the polities of

the pre-Islamic Sasanians of Iran and of certain

early Islamic rulers. Under the successors of Toghrl,

especially Alp-Arslan and Malik-Shah,

the so-called Great Seljuq empire did attain a certain

degree of centralization, and the sultans and princes went on to conquer

eastern and central Anatolia in the name of Islam and to

eject the Shi'ite Fatimids from Syria.

In the second half of the 11th and the first half of the 12th century,

the Seljuq Turks gradually established more or less

direct rule over all of Arabian Iraq. The 'Uqaylids of

Upper Iraq were finally overthrown by Taj ad-Dawlah Tutush

(1077-1095) of the Syrian branch of the Seljuq

family. Upper Iraq now came under the rule of Seljuq

princes and their governors, who were often of servile origin. One of

these governors, 'Imad ad-Din Zangi, with the decline of

the power of his Seljuq masters, founded an independent dynasty, the

Zangids. A branch of the Zangid dynasty

ruled Mosul from 1127 to 1222. At the time of the

Mongol invasions, Mosul was in the hands of the

slave general Badr ad-Din Lu'lu' (1222-59). In Lower Iraq

the Mazyadids were able to extend their influence; in the

early 1100s they took the towns of Hit, Wasit,

Basra, and Tikrit. In 1108, however,

their king, Sadaqah, was defeated and killed by the

Seljuq sultan Muhammad Tapar (1105-18), and the dynasty

never regained its former importance. The Mazyadids were

finally dispossessed by the Seljuqs in the second half of

the 12th century, and their capital, Al-Hillah, was

occupied by caliphal forces.

The later 'Abbasids period (1152-1258)

With the death of Muhammad Tapar, the Great

Seljuq state was in effect partitioned between Muhammad's brother

Sanjar, headquartered at Marw in

Khorasan, and his son Mahmud II (1118-31),

centred on Hamadan in Persian Iraq. These Iraq Seljuq

sultans tried unsuccessfully to maintain their control over the 'Abbasid

caliph in Baghdad, but in 1135 the caliph al-Mustarshid

(1118-35) personally led an army against the sultan Mas'ud,

although he was defeated and later assassinated. Al-Mustarshid's

brother, al-Muqtafi (1136-60), was appointed by Sultan

Mas'ud to succeed him as caliph. After Mas'ud's

death, al-Muqtafi was able to establish a "caliphal"

state based on Baghdad by conquering Al-Hillah,

Al-Kufah, Wasit, and Tikrit.

By far the most important figure in the revival of independent caliphal

authority in Arabian Iraq and the surrounding area--after more than 200

years of "secular" military domination, first under the Buyids

and then the Seljuqs--was the caliph an-Nasir

(1180-1225). For nearly half a century, he tried to rally the Islamic

world under the banner of 'Abbasid universalism, not only politically, by

emphasizing the necessity for the support of caliphal causes, but also

morally, by attempting to reconcile the Sunnites and the Shi'ites. In

addition, he tried to gain control of various voluntary associations such

as the mystico-religious (Sufi) brotherhoods and the

craft-associated (futuwah) organizations. He also began

the dangerous precedent of allying himself with powers in Khorasan

and Central Asia against the traditional caliphal adversaries in Persian

Iraq. Through this policy, he was able to rid himself of the last Iraq

Seljuq sultan, Toghrl III (1176-94), who

was killed by the Khwarezm-Shah 'Ala' ad-Din Tekish

(1172-1200), the ruler of the province lying along the lower course of the

Amu Darya (ancient Oxus River) in Central Asia.

When Tekish insisted on greater formal recognition

from the caliph a few years later, an-Nasir refused, and

inconclusive fighting broke out between the two. The conflict came to a

head under Tekish's son, the Khwarezm-Shah 'Ala'

ad-Din Muhammad (1200-20), who demanded that the caliph renounce

the temporal power built up by the later 'Abbasids after the decline of

the Iraq Seljuqs. When negotiations broke down,

Muhammad declared an-Nasir deposed, proclaimed

an eastern Iranian notable as anticaliph, and marched on Baghdad.

In 1217 Muhammad seized most of western Iran, but, just

as he was about to fall on an-Nasir's capital, his army

was decimated by a blizzard in the Zagros Mountains. These events afforded

an-Nasir and his successors only a brief respite from

dangers arising in the east.

Visit photo

gallery, for further related images