Visit photo

gallery, for further related images

Early history of Assyria

Strictly speaking, the use of the name "Assyria"

for the period before the latter half of the 2nd millennium BC is

anachronistic; Assyria [as against the city-state

of Ashur] did not become an independent state

until about 1400 BC. For convenience, however, the term

is used throughout this section. In contrast to southern

Mesopotamia or the mid-Euphrates region (Mari),

written sources in Assyria do not begin until very late,

shortly before Ur III. By Assyria (

a region that does not lend itself to precise geographic

delineation) is understood the territory on the Tigris

north of the river's passage through the mountains of the Jabal

Hamrin to a point north of Nineveh, as well as

the area between Little and Great Zab (a

tributary of the Tigris in northeast Iraq)

and to the north of the latter. In the north, Assyria was

later bordered by the mountain state of Urartu; to the

east and southeast its neighbor was the region around ancient

Nuzi (near modern Kirkuk, "Arrapchitis"

[Arrapkha] of the Greeks). In the early 2nd millennium

the main cities of this region were Ashur (160 miles

north-northwest of modern Baghdad), the capital

(synonymous with the city god and national divinity); Nineveh,

lying opposite modern Mosul; and Urbilum,

later Arbela (modern Irbil, some 200

miles north of Baghdad).

In Assyria, inscriptions were composed

in Akkadian from the beginning. Under Ur III,

Ashur was a provincial capital. Assyria

as a whole, however, is not likely to have been a permanently secured part

of the empire, since two date formulas of Shulgi

and Amar-Su'ena mention the destruction of

Urbilum. Ideas of the population of Assyria in

the 3rd millennium are necessarily very imprecise. It is not known how

long Semitic tribes had been settled there. The

inhabitants of southern Mesopotamia called

Assyria Shubir in

Sumerian and Subartu

in Akkadian; these names may point to a Subarean

population that was related to the Hurrians.

Gasur, the later Nuzi, belonged to the

Akkadian language region about the year 2200 but was lost to the

Hurrians in the first quarter of the 2nd millennium. The

Assyrian dialect of Akkadian found in

the beginning of the 2nd millennium differs strongly from the dialect of

Babylonia. These two versions of the Akkadian

language continue into the 1st millennium.

In contrast to the kings of southern

Mesopotamia, the rulers of Ashur styled

themselves not king but partly issiakum, the

Akkadian equivalent of the Sumerian word

ensi, partly ruba'um, or "great one."

Unfortunately, the rulers cannot be synchronized precisely with the kings

of southern Mesopotamia before Shamshi-Adad I

(c. 1813-c. 1781 BC). For instance, it has not yet been

established just when Ilushuma's excursion toward the

southeast, recorded in an inscription, actually took place.

Ilushuma boasts of having freed of taxes the "Akkadians

and their children." While he mentions the cities of

Nippur and Ur, the other localities listed were

situated in the region east of the Tigris. The event

itself may have taken place in the reign of Ishme-Dagan

of Isin (c. 1953-c. 1935 BC), although how far

Ilushuma's words correspond to the truth cannot be checked. In

the Babylonian texts, at any rate, no reference is made

to Assyrian intervention. The whole problem of dating is

aggravated by the fact that the Assyrians did not, unlike

the Babylonians, use date formulas that often contain

interesting historical details; instead, every year was designated by the

name of a high official (eponymic

dating). The conscious cultivation of an old

tradition is mirrored in the fact that two rulers of 19th-century

Assyria called themselves Sargon and

Naram-Sin after famous models in the Akkadian dynasty.

Aside from the generally scarce reports on projected

construction, there is at present no information about the city of

Ashur and its surroundings. There exists, however, unexpectedly

rewarding source material from the trading colonies of Ashur

in Anatolia. The texts come mainly from Kanesh

(modern Kültepe, near Kayseri, in

Turkey) and from Hattusa (modern

Bogazköy, Turkey.), the later Hittite

capital. In the 19th century BC three generations of Assyrian

merchants engaged in a lively commodity trade (especially

in textiles and metal) between the

homeland and Anatolia, also taking part profitably in

internal Anatolian trade. Like their contemporaries in

southern Mesopotamia, they did business privately

and at their own risk, living peacefully and occasionally intermarrying

with the "Anatolians." As long as they paid taxes to the

local rulers, the Assyrians were given a free hand.

Clearly these forays by Assyrian

merchants led to some transplanting of Mesopotamian culture

into Anatolia. Thus the Anatolians

adopted cuneiform writing and used the Assyrian

language. While this influence doubtless already affected the

first Hittites arriving in Anatolia, a

direct line from the period of these trading colonies to

the Hittite empire cannot yet be traced.

From about 1813 to about 1781 Assyria

was ruled by Shamshi-Adad I, a contemporary of

Hammurabi and a personality in no way inferior to him.

Shamshi-Adad's father [an Amorite, to judge by

the name] had ruled near Mari. The son, not being of

Assyrian origin, ascended the throne of Assyria

as a foreigner and on a detour, as it were, after having spent some time

as an exile in Babylonia. He had his two sons rule as

viceroys, in Ekallatum on the Tigris and

in Mari, respectively, until the older of the two,

Ishme-Dagan, succeeded his father on the throne. Through

the archive of correspondence in the palace at Mari,

scholars are particularly well informed about Shamshi-Adad's

reign and many aspects of his personality. Shamshi-Adad's

state had a common border for some time with the Babylonia

of Hammurabi. Soon after Shamshi-Adad's

death, Mari broke away, regaining its independence under

an Amorite dynasty that had been living there for

generations; in the end, Hammurabi conquered and

destroyed Mari. After Ishme-Dagan's

death, Assyrian history is lost sight of for more than

100 years.

The rise of Assyria

Very little can be said about northern Assyria

during the 2nd millennium BC. Information on the old capital,

Ashur, located in the south of the country, is somewhat more

plentiful. The old lists of kings suggest that the same

dynasty ruled continuously over Ashur from about 1600.

All the names of the kings are given, but little else is known about

Ashur before 1420. Almost all the princes had

Akkadian names, and it can be assumed that their sphere of

influence was rather small. Although Assyria belonged to

the kingdom of the Mitanni for a long time, it seems that

Ashur retained a certain autonomy.

Located close to the boundary with Babylonia, it played

that empire off against Mitanni whenever possible.

Puzur-Ashur III concluded a border treaty with

Babylonia about 1480, as did Ashur-bel-nisheshu

about 1405. Ashur-nadin-ahhe II (c. 1392-c. 1383) was

even able to obtain support from Egypt, which sent him a

consignment of gold.

Ashur-uballit I

(c. 1354-c. 1318) was

at first subject to King Tushratta of Mitanni.

After 1340, however, he attacked Tushratta, presumably

together with Suppiluliumas I of the Hittites.

Taking away from Mitanni parts of northeastern

Mesopotamia, Ashur-uballit now called himself "Great

King" and socialized with the king of Egypt on

equal terms, arousing the indignation of the king of Babylonia.

Ashur-uballit was the first to name Assyria

the Land of Ashur, because

the old name, Subartu, was often used in a derogatory

sense in Babylonia. He ordered his short inscriptions to

be partly written in the Babylonian dialect rather than

the Assyrian, since this was considered refined. Marrying

his daughter to a Babylonian, he intervened there

energetically when Kassite nobles murdered his grandson.

Future generations came to consider him rightfully as the real founder of

the Assyrian empire. His son Enlil-nirari

(c. 1326-c. 1318) also fought against Babylonia.

Arik-den-ili (c. 1308-c. 1297) turned westward, where he

encountered Semitic tribes of the so-called

Akhlamu group.

Still greater successes were achieved by

Adad-nirari I (c. 1295-c. 1264). Defeating the Kassite

king Nazimaruttash, he forced him to retreat. After that

he defeated the kings of Mitanni, first Shattuara

I, then Wasashatta. This enabled him for a time

to incorporate all Mesopotamia into his empire as a

province, although in later struggles he lost large parts to the

Hittites. In the east, he was satisfied with the defense of his

lands against the mountain tribes.

Adad-nirari's inscriptions were more

elaborate than those of his predecessors and were written in the

Babylonian dialect. In them he declares that he feels called to

these wars by the gods, a statement that was to be repeated by other kings

after him. Assuming the old title of great king, he

called himself "King of All." He enlarged the

temple and the palace in Ashur

and also developed the fortifications there, particularly at the banks of

the Tigris River. He worked on large building projects in

the provinces.

His son Shalmaneser I (Shulmanu-asharidu;

c. 1263-c. 1234) attacked Uruatru (later called Urartu)

in southern Armenia, which had allegedly broken away.

Shattuara II of Hanigalbat, however, put

him into a difficult situation, cutting his forces off from their water

supplies. With courage born of despair, the Assyrians

fought themselves free. They then set about reducing what was left of the

Mitanni kingdom into an Assyrian province.

The king claimed to have blinded 14,400 enemies in one eye [psychological

warfare of a similar kind was used more and more as time went by].

The Hittites tried in vain to save Hanigalbat.

Together with the Babylonians they fought a

commercial war against Ashur for many years.

Like his father, Shalmaneser was a great builder. At the

juncture of the Tigris and Great Zab

rivers, he founded a strategically situated second capital, Kalakh

(biblical Calah; modern Nimrud).

His son was Tukulti-Ninurta (c.

1233-c. 1197), the Ninus of Greek legends.

Gifted but extravagant, he made his nation a great power. He carried off

thousands of Hittites from eastern Anatolia.

He fought particularly hard against Babylonia, deporting

Kashtiliash IV to Assyria. When the

Babylonians rebelled again, he plundered the

temples in Babylon, an act regarded as a

sacrilege, even in Assyria. The relationship between the

king and his capital deteriorated steadily. For this reason the king began

to build a new city, Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta, on the other

side of the Tigris River. Ultimately, even his sons

rebelled against him and laid siege to him in his city; in the end he was

murdered. His victorious wars against Babylonia were

glorified in an epic poem, but his empire broke up soon

after his death. Assyrian power declined for a time,

while that of Babylonia rose.

Assyria had suffered under the

oppression of both the Hurrians and the Mitanni

kingdom. Its struggle for liberation and the bitter wars that

followed had much to do with its development into a military power.

In his capital of Ashur, the king depended on the

citizen class and the priesthood, as well as on

the landed nobility that furnished him with the

war-chariot troops.

Documents and letters show the important role that

agriculture played in the development of the state.

Assyria was less dependent on artificial

irrigation than was Babylonia. The breeding of

horses was carried on intensively; remnants of elaborate

directions for their training are extant. Trade and commerce also were of

notable significance: metals were imported

from Anatolia or Armenia, tin

from northwestern Iran, and lumber from

the west. The opening up of new trade routes was often a cause and the

purpose of war.

Assyrian architecture, derived from a

combination of Mitannian and Babylonian

influences, developed early quite an individual style. The palaces

often had colorful wall decorations. The art of seal cutting,

taken largely from Mitanni, continued creatively on its

own. The schools for scribes, where all the civil

servants were trained, taught both the Babylonian

and the Assyrian dialects of the Akkadian

language. Babylonian works of literature

were assimilated into Assyrian, often reworked into a

different form. The Hurrian tradition remained strong in

the military and political sphere while at the same time influencing the

vocabulary of language.

Assyria between 1200 and 1000 BC

After a period of decline following

Tukulti-Ninurta I, Assyria was consolidated and

stabilized under Ashur-dan I (c. 1179-c. 1134) and

Ashur-resh-ishi I (c. 1133-c. 1116). Several times forced

to fight against Babylonia, the latter was even able to

defend himself against an attack by Nebuchadrezzar I.

According to the inscriptions, most of his building efforts were in

Nineveh, rather than in the old capital of Ashur.

His son Tiglath-pileser I (Tukulti-apil-Esharra;

c. 1115-c. 1077) raised the power of Assyria to new

heights. First he turned against a large army of the Mushki

that had entered into southern Armenia from

Anatolia, defeating them decisively. After this, he forced the

small Hurrian states of southern Armenia

to pay him tribute. Trained in mountain warfare themselves and helped by

capable pioneers, the Assyrians were now able to advance

far into the mountain regions. Their main enemies were the

Aramaeans, the Semitic Bedouin nomads whose many

small states often combined against the Assyrians.

Tiglath-pileser I also went to Syria and

even reached the Mediterranean, where he took a sea

voyage. After 1100 these campaigns led to conflicts with Babylonia.

Tiglath-pileser conquered northern Babylonia

and plundered Babylon, without decisively defeating

Marduk-nadin-ahhe. In his own country the king paid

particular attention to agriculture and fruit

growing, improved the administrative system, and

developed more thorough methods of training scribes.

Three of his sons reigned after Tiglath-pileser,

including Ashur-bel-kala (c. 1074-c. 1057). Like his

father, he fought in southern Armenia and against the

Aramaeans with Babylonia as his ally.

Disintegration of the empire could not be delayed, however. The grandson

of Tiglath-pileser, Ashurnasirpal I (c.

1050-c. 1032), was sickly and unable to do more than defend

Assyria proper against his enemies. Fragments of three of his

prayers to Ishtar are preserved; among them is a

penitential prayer in which he wonders about the cause of so much

adversity. Referring to his many good deeds but admitting his guilt at the

same time, he asks for forgiveness and health. According to the king, part

of his guilt lay in neglecting to teach his subjects the fear of

god. After him, little is known for 100 years.

Three of his sons reigned after Tiglath-pileser,

including Ashur-bel-kala (c. 1074-c. 1057). Like his

father, he fought in southern Armenia and against the

Aramaeans with Babylonia as his ally.

Disintegration of the empire could not be delayed, however. The grandson

of Tiglath-pileser, Ashurnasirpal I (c.

1050-c. 1032), was sickly and unable to do more than defend

Assyria proper against his enemies. Fragments of three of his

prayers to Ishtar are preserved; among them is a

penitential prayer in which he wonders about the cause of so much

adversity. Referring to his many good deeds but admitting his guilt at the

same time, he asks for forgiveness and health. According to the king, part

of his guilt lay in neglecting to teach his subjects the fear of

god. After him, little is known for 100 years.

State and society

during the time of Tiglath-pileser were not essentially

different from those of the 13th century. Collections of laws, drafts, and

edicts of the court exist that go back as far as the 14th century BC.

Presumably, most of these remained in effect. One tablet defining the

marriage laws shows that the social position

of women in Assyria was lower than in Babylonia

or among the Hittites. A man was allowed to send away his

wife at his own pleasure with or without divorce money.

In the case of adultery, he was permitted to kill or maim

her. Outside her house the woman was forced to observe many restrictions,

such as the wearing of a veil. It is not clear whether

these regulations carried the weight of law, but they

seem to have represented a reaction against practices that were more

favorable to women. Two somewhat older marriage contracts,

for example, granted equal rights to both

partners, even in divorce. The women of the

king's harem were subject to severe punishment, including beating,

maiming, and death, along with those who guarded and looked after them.

The penal laws of the time were generally more severe in Assyria

than in other countries of the East. The death penalty

was not uncommon. In less serious cases the penalty was forced

labor after flogging. In certain cases there

was trial by ordeal. One tablet treats the subject of landed property

rights. Offenses against the established boundary lines called for

extremely severe punishment. A creditor was allowed to force his debtor to

work for him, but he could not sell him.

The greater part of Assyrian literature

was either taken over from Babylonia or written by the

Assyrians in the Babylonian dialect, who

modeled their works on Babylonian originals. The

Assyrian dialect was used in legal documents,

court and temple rituals, and

collections of recipes--as, for example, in directions

for making perfumes. A new art form was

the picture tale: a continuing series of pictures

carved on square stela of stone. The pictures, showing war or hunting

scenes, begin at the top of the stela and run down around it, with

inscriptions under the pictures explaining them. These and the finely

cut seals show that the fine arts of Assyria

were beginning to surpass those of Babylonia.

Architecture and other forms of the monumental arts also began a

further development, such as the double temple with its

two towers (ziggurat). Colorful enameled tiles were used

to decorate the facades.

Assyria and Babylonia from c. 1000 to c. 750 BC

Assyria and Babylonia

until Ashurnasirpal II

The most important factor in the history of

Mesopotamia in the 10th century was the continuing threat from

the Aramaean seminomads. Again and again, the kings of

both Babylonia and Assyria were forced

to repel their invasions. Even though the Aramaeans were

not able to gain a foothold in the main cities, there are evidences of

them in many rural areas. Ashur-dan II (934-912)

succeeded in suppressing the Aramaeans and the

mountain people, in this way stabilizing the Assyrian

boundaries. He reintroduced the use of the Assyrian dialect

in his written records.

Adad-nirari II (c. 911-891) left

detailed accounts of his wars and his efforts to improve

agriculture. He led six campaigns against Aramaean

intruders from northern Arabia. In two campaigns against

Babylonia he forced Shamash-mudammiq (c.

930-904) to surrender extensive territories. Shamash-mudammiq

was murdered, and a treaty with his successor, Nabu-shum-ukin

(c. 904-888), secured peace for many years.

Tukulti-Ninurta II (c. 890-884), the son of Adad-nirari

II, preferred Nineveh to Ashur.

He fought campaigns in southern Armenia. He was portrayed

on stela in blue and yellow enamel in the late Hittite style,

showing him under a winged sun. His son

Ashurnasirpal II (883-859) continued the policy of

conquest and expansion. He left a detailed

account of his campaigns, which were impressive in their cruelty. Defeated

enemies were impaled, flayed, or

beheaded in great numbers. Mass deportations,

however, were found to serve the interests of the growing empire

better than terror. Through the systematic exchange of native

populations, conquered regions were denationalized. The

result was a submissive, mixed population in which the

Aramaean element became the majority. This provided the

labor force for the various public works in the metropolitan centres of

the Assyrian empire. Ashurnasirpal II

rebuilt Kalakh, founded by Shalmaneser I,

and made it his capital. Ashur remained the centre of the

worship of the god Ashur--in whose name all the wars of

conquest were fought. A third capital was Nineveh.

Ashurnasirpal II was the first to use

cavalry units to any large extent in addition to

infantry and war-chariot troops. He also was the

first to employ heavy, mobile battering rams

and wall breakers in his sieges. Following after the

conquering troops came officials from all branches of the civil

service, because the king wanted to lose no time in incorporating

the new lands into his empire. The supremacy of

Assyria over its neighboring states owed much to the proficiency

of the government service under the leadership of the minister

Gabbilani-eresh. The campaigns of Ashurnasirpal II

led him mainly to southern Armenia and

Mesopotamia. After a series of heavy wars, he incorporated

Mesopotamia as far as the Euphrates

River. A campaign to Syria encountered little resistance.

There was no great war against Babylonia.

Ashurnasirpal, like other Assyrian kings, may

have been moved by religion not to destroy

Babylonia, which had almost the same gods as

Assyria. Both empires must have profited from

mutual trade and cultural exchange. The

Babylonians, under the energetic Nabu-apla-iddina

(c. 887-855) attacked the Aramaeans in southern

Mesopotamia and occupied the valley of the Euphrates

River to about the mouth of the Khabur River.

Ashurnasirpal, so brutal in his wars,

was able to inspire architects, structural

engineers, and artists and sculptors

to heights never before achieved. He built and enlarged temples

and palaces in several cities. His most impressive

monument was his own palace in Kalakh,

covering a space of 269,000 square feet (25,000 square meters). Hundreds

of large limestone slabs were used in murals in the staterooms and living

quarters. Most of the scenes were done in relief, but painted murals also

have been found. Most of them depict mythological themes

and symbolic fertility rites, with the king

participating. Brutal war pictures were aimed to discourage

enemies. The chief god of Kalakh was

Ninurta, god of war and the hunt. The tower of the temple

dedicated to Ninurta also served as an

astronomical observatory. Kalakh soon became the

cultural centre of the empire. Ashurnasirpal

claimed to have entertained 69,574 guests at the opening ceremonies of his

palace.

Shalmaneser III and Shamshi-Adad V of Assyria

The son and successor of Ashurnasirpal

was Shalmaneser III (858-824). His father's equal in both

brutality and energy, he was less realistic in his undertakings. His

inscriptions, in a peculiar blend of Assyrian and

Babylonian, record his considerable achievements but are not

always able to conceal his failures. His campaigns were directed mostly

against Syria. While he was able to conquer

northern Syria and make it a province, in the

south he could only weaken the strong state of Damascus

and was unable, even after several wars, to eliminate it. In 841 he laid

unsuccessful siege to Damascus. Also in 841 King

Jehu of Israel was forced to pay tribute. In his

invasion of Cilicia, Shalmaneser had

only partial success. The same was true of the kingdom of Urartu

in Armenia, from which, however, the troops returned with

immense quantities of lumber and building stone.

The king and, in later years, the general Dayyan-Ashur

went several times to western Iran, where they found such

states as Mannai in northwestern Iran

and, farther away in the southeast, the Persians. They

also encountered the Medes during these wars.

Horse tribute was collected.

In Babylonia,

Marduk-zakir-shumi I ascended the throne about the year 855. His

brother Marduk-bel-usati rebelled against him, and in 851

the king was forced to ask Shalmaneser for help.

Shalmaneser was only too happy to oblige; when the usurper had

been finally eliminated (850), Shalmaneser went to

southern Babylonia, which at that time was almost

completely dominated by Aramaeans. There he encountered,

among others, the Chaldeans, mentioned for the first time

in 878 BC, who were to play a leading role in the history

of later times; Shalmaneser made them tributaries.

During his long reign he built temples,

palaces, and fortifications in

Assyria as well as in the other capitals of his provinces. His

artists created many statues and stela.

Among the best known is the Black Obelisk, which includes

a picture of Jehu of Israel paying

tribute. The bronze doors from the town of Imgur-Enlil (Balawat)

in Assyria portray the course of his campaigns and other

undertakings in rows of pictures, often very lifelike. Hundreds of

delicately carved ivories were carried away from

Phoenicia, and many of the artists along with them; these later

made Kalakh a centre for the art of ivory

sculpture.

In the last four years of the reign of

Shalmaneser, the crown prince Ashur-da'in-apla

led a rebellion. The old king appointed his younger son

Shamshi-Adad as the new crown prince. Forced to flee to

Babylonia, Shamshi-Adad V (823-811) finally

managed to regain the kingship with the help of Marduk-zakir-shumi

I under humiliating conditions. As king he campaigned with

varying success in southern Armenia and

Azerbaijan, later turning against Babylonia. He

won several battles against the Babylonian kings

Marduk-balassu-iqbi and Baba-aha-iddina (about

818-12) and pushed through to Chaldea. Babylonia

remained independent, however.

Adad-nirari III and his successors

Shamshi-Adad V died while

Adad-nirari III (810-783) was still a minor. His

Babylonian mother, Sammu-ramat, took over the

regency, governing with great energy until 806. The

Greeks, who called her Semiramis,

credited her with legendary accomplishments, but historically little is

known about her. Adad-nirari later led several campaigns

against the Medes and also against Syria

and Palestine. In 804 he reached Gaza,

but Damascus proved invincible. He also fought in

Babylonia, helping to restore order in the north.

Shalmaneser IV (c. 783-773) fought

against Urartu, then at the height of its power under

King Argishti (c. 780-755). He successfully defended

eastern Mesopotamia against attacks from Armenia.

On the other hand, he lost most of Syria after a campaign

against Damascus in 773. The reign of Ashur-dan

III (772-755) was shadowed by rebellions and by epidemics of

plague. Of Ashur-nirari V (754-746)

little is known.

In Assyria the feudal

structure of society remained largely unchanged. Many of the conquered

lands were combined to form large provinces. The governors of these

provinces sometimes acquired considerable independence, particularly under

the weaker monarchs after Adad-nirari III. Some of them

even composed their own inscriptions. The influx of displaced peoples into

the cities of Assyria created large metropolitan

centers. The spoils of war, together with an expanding

trade, favored the development of a well-to-do

commercial class. The dense population of the cities gave rise to

social tensions that only the strong kings were able to contain. A number

of the former capitals of the conquered lands remained important as

capitals of provinces. There was much new building. A standing

occupational force was needed in the provinces, and these troops grew

steadily in proportion to the total military forces. There are no records

on the training of officers or on military logistics. The civil

service also expanded, the largest administrative

body being the royal court, with thousands of

functionaries and craftsmen in the several residential cities.

The cultural decline about the year

1000 was overcome during the reigns of

Ashurnasirpal II and Shalmaneser III. The

arts in particular experienced a tremendous resurgence.

Literary works continued to be written in

Assyrian and were seldom of great importance. The literature that

had been taken over from Babylonia was further developed

with new writings, although one can rarely distinguish between works

written in Assyria and works written in Babylonia.

In religion, the official cults of Ashur and

Ninurta continued, while the religion of the

common people went its separate way.

In Babylonia not much was left of the

feudal structure; the large landed estates almost

everywhere fell prey to the inroads of the Aramaeans, who

were at first half nomadic. The leaders of their tribes

and clans slowly replaced the former landlords. Agriculture

on a large scale was no longer possible except on the outskirts of

metropolitan areas. The predominance of the Babylonian

schools for scribes may have prevented the

emergence of an Aramaean literature. In any case, the

Aramaeans seem to have been absorbed

into the Babylonian culture. The religious cults

in the cities remained essentially the same. The Babylonian empire

was slowly reduced to poverty, except perhaps in some of the cities.

In 764, after an epidemic, the

Erra epic, the myth of Erra (the god of war and

pestilence), was written by Kabti-ilani-Marduk. He

invented an original plot, which diverged considerably from the old myths;

long discourses of the gods involved in the action form the most important

part of the epic. There is a passage in the epic claiming that the text

was divinely revealed to the poet during a dream.

The Neo-Assyrian Empire (746-609)

For no other period of Assyrian

history is there an abundance of sources comparable to those available for

the interval from roughly 745 to 640. Aside from the large number of

royal inscriptions, about 2,400 letters, most of them

more or less fragmentary, have been published. Usually the senders and

recipients of these letters are the king and high government officials.

Among them are reports from royal agents about

foreign affairs and letters about cultic matters.

Treaties, oracles, queries

to the sun god about political matters, and

prayers of or for kings contain a great deal of additional

information. Last but certainly not least are paintings

and wall relief's, which are often very informative.

Tiglath-pileser III

and Shalmaneser V

The decline of Assyrian power after

780 was notable; Syria and considerable lands in the

north were lost. A military coup deposed King

Ashur-nirari V and raised a general to the

throne. Under the name of Tiglath-pileser III (745-727),

he brought the empire to its greatest expanse. He reduced

the size of the provinces in order to break the partial independence of

the governors. He also invalidated the tax privileges of

cities such as Ashur and Harran in order

to distribute the tax load more evenly over the entire realm.

Military equipment was improved substantially. In 746 he went to

Babylonia to aid Nabu-nasir (747-734) in

his fight against Aramaean tribes.

Tiglath-pileser defeated the Aramaeans and then

made visits to the large cities of Babylonia. There he

tried to secure the support of the priesthood by

patronizing their building projects. Babylonia retained

its independence.

His next undertaking was to check Urartu.

His campaigns in Azerbaijan were designed to drive a

wedge between Urartu and the Medes. In

743 he went to Syria, defeating there an army of

Urartu. The Syrian city of Arpad,

which had formed an alliance with Urartu, did not

surrender so easily. It took Tiglath-pileser three years

of siege to conquer Arpad, whereupon he massacred the

inhabitants and destroyed the city. In 738 a new coalition formed against

Assyria under the leadership of Sam'al

(modern Zincirli) in northern Syria. It

was defeated, and all the princes from Damascus to

eastern Anatolia were forced to pay tribute. Another

campaign in 735, this time directed against Urartu

itself, was only partly successful. In 734 Tiglath-pileser

invaded southern Syria and the Philistine

territories in Palestine, going as far as the

Egyptian border. Damascus and Israel

tried to organize resistance against him, seeking to bring Judah

into their alliance. Ahaz of Judah, however, asked

Tiglath-pileser for help. In 733 Tiglath-pileser

devastated Israel and forced it to surrender large

territories. In 732 he advanced upon Damascus, first

devastating the gardens outside the city and then conquering the capital

and killing the king, whom he replaced with a governor. The queen of

southern Arabia, Samsil, was now obliged

to pay tribute, being permitted in return to use the harbor of the city

of Gaza, which was in Assyrian hands.

The death of King Nabonassar of

Babylonia caused a chaotic situation to develop there,

and the Aramaean Ukin-zer crowned

himself king. In 731 Tiglath-pileser fought and beat him

and his allies, but he did not capture Ukin-zer until

729. This time he did not appoint a new king for Babylonia

but assumed the crown himself under the name Pulu (Pul in

the Old Testament). In his old age he abstained from further campaigning,

devoting himself to the improvement of his capital, Kalakh.

He rebuilt the palace of Shalmaneser III, filled it with

treasures from his wars, and decorated the walls with bas-reliefs. The

latter were almost all of warlike character, as if designed to intimidate

the onlooker with their presentation of gruesome executions. These

pictorial narratives on slabs, sometimes painted, have also been found in

Syria, at the sites of several provincial capitals of

ancient Assyria.

Tiglath-pileser was succeeded by his

son Shalmaneser V (726-722), who continued the policy of

his father. As king of Babylonia, he called himself

Ululai. Almost nothing is known about his enterprises,

since his successor destroyed all his inscriptions. The Old

Testament relates that he marched against Hoshea

of Israel in 724 after Hoshea had

rebelled. He was probably assassinated during the long siege of

Samaria. His successor maintained that the god Ashur

had withdrawn his support of Shalmaneser V for acts of

disrespect.

Sargon II (721-705) and Marduk-apal-iddina of Babylonia

It was probably a younger brother of

Shalmaneser who ascended the throne of Assyria

in 721. Assuming the old name of Sharru-kin (Sargon in

the Bible), meaning "Legitimate King," he assured himself

of the support of the priesthood and the merchant

class by restoring privileges they had lost, particularly the tax

exemptions of the great temples. The change of sovereign

in Assyria triggered another crisis in Babylonia.

An Aramaean prince from the south,

Marduk-apal-iddina II (the biblical Merodach-Baladan),

seized power in Babylon in 721 and was able to retain it

until 710 with the help of Humbanigash I of Elam.

A first attempt by Sargon to recover Babylonia

miscarried when Elam defeated him in 721. During the same

year the protracted siege of Samaria was brought to a

close. The Samarian upper class was deported, and

Israel became an Assyrian province.

Samaria was repopulated with Syrians and

Babylonians. Judah remained independent by

paying tribute. In 720 Sargon squelched

a rebellion in Syria that had been supported by

Egypt. Then he defeated both Hanunu of

Gaza and an Egyptian army near the

Egyptian border. In 717 and 716 he campaigned in northern

Syria, making the hitherto independent state of

Carchemish one of his provinces. He also went to Cilicia

in an effort to prevent further encroachments of the Phrygians

under King Midas (Assyrian: Mita).

In order to protect his ally, the state of

Mannai, in Azerbaijan, Sargon

embarked on a campaign in Iran in 719 and incorporated

parts of Media as provinces of his empire; however, in

716 another war became necessary. At the same time, he was busy preparing

a major attack against Urartu. Under the leadership of

the crown prince Sennacherib, armies of agents

infiltrated Urartu, which was also threatened from the

north by the Cimmerians. Many of their messages and

reports have been preserved. The longest inscription ever composed by the

Assyrians about a year's enterprise (430 very long lines)

is dedicated to this Urartu campaign of 714. Phrased in

the style of a first report to the god Ashur, it is

interspersed with stirring descriptions of natural scenery. The strong

points of Urartu must have been well fortified.

Sargon tried to avoid them by going through the province of

Mannai and attacking the Median

principalities on the eastern side of Lake Urmia. In the

meantime, hoping to surprise the Assyrian troops,

Rusa of Urartu had closed the narrow pass lying

between Lake Urmia and Sahand Mount.

Sargon, anticipating this, led a small band of

cavalry in a surprise charge that developed into a great victory

for the Assyrians. Rusa fled and died.

The Assyrians pushed forward, destroying all the cities,

fortifications, and even irrigation works of Urartu. They

did not conquer Tushpa (the capital) but took possession

of the mountain city of Musasir. The spoils were immense.

The following years saw only small campaigns in Media and

eastern Anatolia and against Ashdod, in

Palestine. King Midas of Phrygia

and some cities on Cyprus were quite ready to pay

tribute.

Sargon was now free to settle accounts

with Marduk-apal-iddina of Babylonia.

Abandoned by his ally Shutruk-Nahhunte II of Elam,

Marduk-apal-iddina found it best to flee, first to his

native land on the Persian Gulf and later to Elam.

Because the Aramaean prince had made himself very

unpopular with his subjects, Sargon was hailed as the

liberator of Babylonia. He complied with the wishes of

the priesthood and at the same time put down the

Aramaean nobility. He was satisfied with the modest title of

governor of Babylonia.

At first Sargon resided in

Kalakh, but he then decided to found an entirely new capital

north of Nineveh. He called the city

Dur-Sharrukin--"Sargonsburg" (modern Khorsabad).

He erected his palace on a high terrace in the

northeastern part of the city. The temples of the main

gods, smaller in size, were built within the palatial rectangle, which was

surrounded by a special wall. This arrangement enabled Sargon

to supervise the priests better than had been possible in

the old, large temple complexes. One consequence of this

design was that the figure of the king pushed the gods somewhat into the

background, thereby gaining in importance. Desiring that his palace match

the vastness of his empire, Sargon planned it in

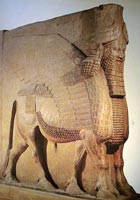

monumental dimensions. Stone relief's of two winged bulls

with human heads flanked the entrance ; they were much larger than

anything comparable built before. The walls were decorated with long rows

of bas-reliefs showing scenes of war and festive processions. A comparison

with a well-executed stela of the Babylonian king

Marduk-apal-iddina shows that the fine arts of

Assyria had far surpassed those of Babylonia.

Sargon never completed his capital, though from 713 to

705 BC tens of thousands of laborers and hundreds of artisans worked on

the great city. Yet, with the exception of some magnificent buildings for

public officials, only a few durable edifices were completed in the

residential section. In 705, in a campaign in northwestern Iran,

Sargon was ambushed and killed. His corpse remained

unburied, to be devoured by birds of prey. Sargon's son

Sennacherib, who had quarreled with his father, was

inclined to believe with the priests that his death was a

punishment from the neglected gods of the ancient

capitals.

Sennacherib (704-681)

Sennacherib (Assyrian: Sin-ahhe-eriba;

704-681) was well prepared for his position as sovereign. With him

Assyria acquired an exceptionally clever and gifted, though often

extravagant, ruler. His father, interestingly enough, is not mentioned in

any of his many inscriptions. He left the new city of

Dur-Sharrukin at once and resided in Ashur for a

few years, until in 701 he made Nineveh his capital.

Sennacherib had considerable

difficulties with Babylonia. In 703

Marduk-apal-iddina again crowned himself king with the aid of

Elam, proceeding at once to ally himself with other

enemies of Assyria. After nine months he was forced to

withdraw when Sennacherib defeated a coalition army

consisting of Babylonians, Aramaeans,

and Elamites. The new puppet king of Babylonia

was Bel-ibni (702-700), who had been raised in

Assyria.

In 702 Sennacherib launched a raid

into western Iran. In 701 there followed his most famous

campaign, against Syria and Palestine,

with the purpose of gaining control over the main road from Syria

to Egypt in preparation for later campaigns against

Egypt itself. When Sennacherib's army

approached, Sidon immediately expelled its ruler,

Luli, who was hostile to Assyria. The other

allies either surrendered or were defeated. An Egyptian

army was defeated at Eltekeh in Judah.

Sennacherib laid siege to Jerusalem, and

the king of Judah, Hezekiah, was called

upon to surrender, but he did not comply. An Assyrian

officer tried to incite the people of Jerusalem against

Hezekiah, but his efforts failed. In view of the

difficulty of surrounding a mountain stronghold such as Jerusalem,

and of the minor importance of this town for the main purpose of the

campaign, Sennacherib cut short the attack and left

Palestine with his army, which according to the

Old Testament (2 Kings 19:35) had been decimated by an

epidemic. The number of Assyrian dead is

reported to have risen to 185,000. Nevertheless, Hezekiah

is reported to have paid tribute to Sennacherib on at

least one occasion.

Bel-ibni

of Babylonia

seceded from the union with Assyria in 700.

Sennacherib moved quickly, defeating Bel-ibni

and replacing him with Sennacherib's oldest son,

Ashur-nadin-shumi. The next few years were relatively peaceful.

Sennacherib used this time to prepare a decisive attack

against Elam, which time and again had supported

Babylonian rebellions. The overland route to Elam

had been cut off and fortified by the Elamites.

Sennacherib had ships built in Syria and at

Nineveh. The ships from Syria were moved

on rollers from the Euphrates to the Tigris.

The fleet sailed downstream and was quite successful in

the lagoons of the Persian Gulf and along the southern

coastline of Elam. The Elamites launched

a counteroffensive by land, occupying Babylonia and

putting a man of their choice on the throne. Not until 693 were the

Assyrians again able to fight their way through to the

north. Finally, in 689, Sennacherib had his revenge.

Babylon was conquered and completely destroyed, the

temples plundered and leveled. The waters of the

Arakhtu Canal were diverted over the ruins, and the inner city

remained almost totally uninhabited for eight years. Even many

Assyrians were indignant at this, believing that the

Babylonian god Marduk must be grievously

offended at the destruction of his temple and the carrying off of his

image. Marduk was also an Assyrian deity,

to whom many Assyrians turned in time of need. A

political-theological propaganda campaign was launched to

explain to the people that what had taken place was in accord with the

wish of most of the gods. A story was written in which Marduk,

because of a transgression, was captured and brought before a tribunal.

Only a part of the commentary to this botched piece of literature is

extant. Even the great poem of the creation of the world,

the Enuma elish, was altered: the god Marduk

was replaced by the god Ashur. Sennacherib's

boundless energies brought no gain to his empire, however, and probably

weakened it. The tenacity of this king can be seen in his building

projects; for example, when Nineveh needed water for

irrigation, Sennacherib had his engineers divert the

waters of a tributary of the Great Zab River. The canal

had to cross a valley at Jerwan. An aqueduct

was constructed, consisting of about two million blocks

of limestone, with five huge, pointed archways over the brook in the

valley. The bed of the canal on the aqueduct was sealed with cement

containing magnesium. Parts of this aqueduct are still standing today.

Sennacherib wrote of these and other technological

accomplishments in minute detail, with illustrations.

Sennacherib built a huge palace in

Nineveh, adorned with relieves, some of them depicting the

transport of colossal bull statues by water and by land. Many of the rooms

were decorated with pictorial narratives in bas-relief telling of war and

of building activities. Considerable advances can be noted in artistic

execution, particularly in the portrayal of landscapes and animals.

Outstanding are the depictions of the battles in the lagoons, the life in

the military camps, and the deportations.

In 681 BC there was a rebellion. Sennacherib

was assassinated by one or two of his sons in the temple of the god

Ninurta at Kalakh. This god, along with

the god Marduk, had been badly treated by

Sennacherib, and the event was widely regarded as punishment of

divine origin.

Esarhaddon

(680-669)

Ignoring the claims of his older brothers, an

imperial council appointed Esarhaddon (Ashur-aha-iddina;

680-669) as Sennacherib's successor. The choice is all

the more difficult to explain in that Esarhaddon, unlike

his father, was friendly toward the Babylonians. It can

be assumed that his energetic and designing mother, Zakutu

(Naqia), who came from Syria or Judah,

used all her influence on his behalf to override the national

party of Assyria. The theory that he was a

partner in plotting the murder of his father is rather improbable; at any

rate, he was able to procure the loyalty of his father's army. His

brothers had to flee to Urartu. In his inscriptions,

Esarhaddon always mentions both his father and

grandfather.

Defining the destruction of Babylon

explicitly as punishment by the god Marduk, the new king

soon ordered the reconstruction of the city. He referred to himself only

as governor of Babylonia and through his policies

obtained the support of the cities of Babylonia. At the

beginning of his reign the Aramaean tribes were still

allied with Elam against him, but Urtaku

of Elam (675-664) signed a peace treaty

and freed him for campaigning elsewhere. In 679 he stationed a garrison at

the Egyptian border, because Egypt,

under the Ethiopian king Taharqa, was

planning to intervene in Syria. He put down with great

severity a rebellion of the combined forces of Sidon,

Tyre, and other Syrian cities. The time

was ripe to attack Egypt, which was suffering under the

rule of the Ethiopians and was by no means a united

country. Esarhaddon's first attempt in 674-673

miscarried. In 671 BC, however, his forces took Memphis,

the Egyptian capital. Assyrian

consultants were assigned to assist the princes of the 22 provinces, their

main duty being the collection of tribute.

Occasional threats came from the mountainous border

regions of eastern Anatolia and Iran.

Pushed forward by the Scythians, the Cimmerians

in northern Iran and Transcaucasia tried

to gain a foothold in Syria and western Iran.

Esarhaddon allied himself with the Scythian

king Partatua by giving him one of his daughters in

marriage. In so doing he checked the movement of the Cimmerians.

Nevertheless, the apprehensions of Esarhaddon can be seen

in his many offerings, supplications, and requests to the sun god. These

were concerned less with his own enterprises than with the plans of

enemies and vassals and the reliability of civil servants. The priestesses

of Ishtar had to reassure Esarhaddon

constantly by calling out to him, "Do not be afraid."

Previous kings, as far as is known, had never needed this kind of

encouragement.

At home Esarhaddon was faced with

serious difficulties from factions in the court. His oldest son had died

early. The national party suspected his second son,

Shamash-shum-ukin, of being too friendly with the

Babylonians; he may also have been considered unequal to the task

of kingship. His third son, Ashurbanipal, was given the

succession in 672, Shamash-shum-ukin remaining crown

prince of Babylonia. This arrangement caused much

dissension, and some farsighted civil servants warned of disastrous

effects. Nevertheless, the Assyrian nobles, priests, and

city leaders were sworn to just such an adjustment of the royal line; even

the vassal princes had to take very detailed oaths of allegiance

to Ashurbanipal, with many curses against perjurers.

Another matter of deep concern for Esarhaddon

was his failing health. He regarded eclipses of the moon

as particularly alarming omens, and, in order to prevent a fatal illness

from striking him at these times, he had substitute kings

chosen who ruled during the three eclipses that occurred during his

12-year reign. The replacement kings died or were

put to death after their brief term of office. During his

off-terms Esarhaddon called himself "Mister

Peasant." This practice implied that the gods could not

distinguish between the real king and a false one [quite contrary to

the usual assumptions of the religion].

Esarhaddon enlarged and improved the

temples in both Assyria and

Babylonia. He also constructed a palace in

Kalakh, using many of the picture slabs of

Tiglath-pileser III. The works that remain are not on the level

of those of either his predecessors or of Ashurbanipal.

He died while on an expedition to put down a revolt in Egypt.

Ashurbanipal (668-627)

and Shamash-shum-ukin (668-648)

Although the death of his father occurred far from

home, Ashurbanipal assumed the kingship as planned. He

may have owed his fortunes to the intercession of his grandmother

Zakutu, who had recognized his superior capacities. He tells of

his diversified education by the priests and his training

in armour-making as well as in other military

arts. He may have been the only king in Assyria

with a scholarly background. As crown prince he also had

studied the administration of the vast empire. The record

notes that the gods granted him a record harvest during the first year of

his reign. There were also good crops in subsequent years. During these

first years he also was successful in foreign policy, and

his relationship with his brother in Babylonia was good.

In 668 he put down a rebellion in Egypt

and drove out King Taharqa, but in 664 the nephew of

Taharqa, Tanutamon, gathered forces for

a new rebellion. Ashurbanipal went to Egypt,

pursuing the Ethiopian prince far into the south. His

decisive victory moved Tyre and other parts of the empire

to resume regular payments of tribute. Ashurbanipal

installed Psamtik (Greek: Psammetichos) as prince

over the Egyptian region of Sais. In 656

Psamtik dislodged the Assyrian garrisons

with the aid of Carian and Ionian

mercenaries, making Egypt again independent.

Ashurbanipal did not attempt to reconqure it. A former

ally of Assyria, Gyges of Lydia,

had aided Psamtik in his rebellion. In return,

Assyria did not help Gyges when he was attacked

by the Cimmerians. Gyges lost his throne

and his life. His son Ardys decided that the payment of

tribute to Assyria was a lesser evil than conquest by the

Cimmerians.

Graver difficulties loomed in southern

Babylonia, which was attacked by Elam in 664.

Another attack came in 653, whereupon Ashurbanipal sent a

large army that decisively defeated the Elamites. Their

king was killed, and some of the Elamite states were

encouraged to secede. Elam was no longer strong enough to

assume an active part on the international scene. This victory had serious

consequences for Babylonia. Shamash-shum-ukin

had grown weary of being patronized by his domineering brother. He formed

a secret alliance in 656 with the Iranians,

Elamites, Aramaeans, Arabs, and

Egyptians, directed against Ashurbanipal.

The withdrawal of defeated Elam from this alliance was

probably the reason for a premature attack by Shamash-shum-ukin

at the end of the year 652, without waiting for the promised assistance

from Egypt. Ashurbanipal, taken by

surprise, soon pulled his troops together. The Babylonian

army was defeated, and Shamash-shum-ukin was surrounded

in his fortified city of Babylon. His allies were not

able to hold their own against the Assyrians.

Reinforcements of Arabian camel troops also were

defeated. The city of Babylon was under siege for three

years. It fell in 648 amid scenes of horrible carnage, Shamash-shum-ukin

dying in his burning palace.

After 648 the Assyrians made a few

punitive attacks on the Arabs, breaking the forward

thrust of the Arab tribes for a long time to come. The

main objective of the Assyrians, however, was a final

settlement of their relations with Elam. The refusal of

Elam in 647 to extradite an Aramaean

prince was used as pretext for a new attack that drove deep into its

territory. The assault on the solidly fortified capital of Susa

followed, probably in 646. The Assyrians destroyed the

city, including its temples and palaces.

Vast spoils were taken. As usual, the upper classes of the land were

exiled to Assyria and other parts of the empire, and

Elam became an Assyrian province.

Assyria had now extended its domain to southwestern

Iran. Cyrus I of Persia

sent tribute and hostages to Nineveh, hoping perhaps to

secure protection for his borders with Media. Little is

known about the last years of Ashurbanipal's reign.

Ashurbanipal left more inscriptions

than any of his predecessors. His campaigns were not always recorded in

chronological order but clustered in groups according to their purpose.

The accounts were highly subjective. One of his most

remarkable accomplishments was the founding of the great palace

library in Nineveh (modern Kuyunjik),

which is today one of the most important sources for the study of ancient

Mesopotamia. The king himself supervised its

construction. Important works were kept in more than one copy, some

intended for the king's personal use. The work of arranging and cataloging

drew upon the experience of centuries in the management of collections in

huge temple archives such as the one in Ashur.

In his inscriptions Ashurbanipal tells of becoming an

enthusiastic hunter of big game, acquiring a taste for it during a fight

with marauding lions. In his palace at Nineveh the long

rows of hunting scenes show what a masterful artist can accomplish in

bas-relief; with these relieves Assyrian art reached its

peak. In the series depicting his wars, particularly the wars fought in

Elam, the scenes are overloaded with human figures. Those

portraying the battles with the Arabian camel troops are

magnificent in execution.

One reason for the durability of the Assyrian

empire was the practice of deporting large numbers of people from

conquered areas and resettling others in their place. This kept many of

the conquered nationalities from regaining their power. Equally important

was the installation in conquered areas of a highly developed

civil service under the leadership of trained officers.

The highest ranking civil servant carried the title of tartan,

a Hurrian word. The tartans also

represented the king during his absence. In descending rank were the

palace overseer, the main cupbearer, the

palace administrator, and the governor of Assyria.

The generals often held high official positions,

particularly in the provinces. The civil service

numbered about 100,000, many of them former inhabitants

of subjugated provinces. Prisoners became slaves but were

later often freed.

No laws are known for the

empire, although documents point to the existence of

rules and standards for justice. Those who broke

contracts were subject to severe penalties, even in cases

of minor importance: the sacrifice of a son or the

eating of a pound of wool and drinking of a great

deal of water afterward, which led to a painful death.

The position of women was inferior, except for the

queen and some priestesses.

As yet there are no detailed studies of the

economic situation during this period. The landed

nobility still played an important role, in conjunction with the

merchants in the cities. The large increase in the supply

of precious metals--received as tribute or taken as spoils--did not

disrupt economic stability in many regions. Stimulated by the patronage of

the kings and the great temples, the arts and

crafts flourished during this period. The policy of resettling

Aramaeans and other conquered peoples in Assyria

brought many talented artists and artisans into

Assyrian cities, where they introduced new styles and techniques.

High-ranking provincial civil servants, who were often

very powerful, saw to it that the provincial capitals also benefited from

this economic and cultural growth.

Harran became the most important city

in the western part of the empire; in

the neighboring settlement of Huzirina (modern

Sultantepe, in northern Syria), the remains of

an important library have been discovered. Very few

Aramaic texts from this period have been found; the

climate of Mesopotamia is not conducive

to the preservation of the papyrus and parchment

on which these texts were written. There is no evidence that a

literary tradition existed in any of the other languages

spoken within the borders of the Assyrian empire at this

time, except in peripheral areas of Syria and

Palestine.

Culturally and economically,

Babylonia lagged behind Assyria in this

period. The wars with Assyria [particularly the

catastrophic defeats of 689 and 648] together with many smaller

tribal wars disrupted trade and

agricultural production. The great Babylonian temples

fared best during this period, since they continued to enjoy the patronage

of the Assyrian monarchs. Only a few documents from the

temples have been preserved, however. There is evidence

that the scribal schools continued to operate, and "Sumerian"

inscriptions were even composed for Shamash-shum-ukin. In

comparison with the Assyrian developments, the

pictorial arts were neglected, and Babylonian artists

may have found work in Assyria.

During this period people began to use the names of

ancestors as a kind of family name; this

increase in family consciousness is probably an indication that the number

of old families was growing smaller. By this time the process of "Aramaicization"

had reached even the oldest cities of Babylonia and

Assyria.

Apparently this era was not very fruitful for

literature either in Babylonia or in

Assyria. In Assyria numerous royal inscriptions,

some as long as 1,300 lines, were among the most important texts; some of

them were diverse in content and well composed. Most of the hymns

and prayers were written in the traditional style.

Many oracles, often of unusual content, were proclaimed

in the Assyrian dialect, most often by the

priestesses of the goddess Ishtar of

Arbela. In Assyria as in Babylonia,

the beginnings of a real historical literature are

observed; most of the authors have remained anonymous up

to the present.

The many gods of the tradition were worshiped in

Babylonia and Assyria in large and small

temples, as in earlier times. Very detailed

rituals regulated the sacrifices, and the

interpretations of the ritual performances in the cultic commentaries were

rather different and sometimes very strange.

On some of the temple towers (ziggurats),

astronomical observatories were installed. The earliest

of these may have been the observatory of the Ninurta temple

at Kalakh in Assyria, which dates back

to the 9th century BC; it was destroyed with the city in 612. The most

important observatory in Babylonia from about 580 was

situated on the ziggurat Etemenanki, a temple of

Marduk in Babylon. In Assyria

the observation of the Sun, Moon, and

stars had already reached a rather high level; the

periodic recurrence of eclipses was established. After

600, astronomical observation and calculations

developed steadily, and they reached their high point after 500, when

Babylonian and Greek astronomers began

their fruitful collaboration. Incomplete astronomical diaries, beginning

in 652 and covering some 600 years, have been preserved.

Decline of the Assyrian empire

Few historical sources remain for the last 30 years of

the Assyrian empire. There are no extant inscriptions of

Ashurbanipal after 640 BC, and the few surviving

inscriptions of his successors contain only vague allusions to political

matters. In Babylonia the silence is almost total until

625 BC, when the chronicles resume. The rapid downfall of

the Assyrian empire was formerly attributed to

military defeat, although it was never clear how the

Medes and the Babylonians alone could have

accomplished this. More recent work has established that after 635 a

civil war occurred, weakening the empire so that it could

no longer stand up against a foreign enemy. Ashurbanipal

had twin sons. Ashur-etel-ilani was appointed successor

to the throne, but his twin brother Sin-shar-ishkun did

not recognize him. The fight between them and their supporters forced the

old king to withdraw to Harran, in 632 at the latest,

perhaps ruling from there over the western part of the

empire until his death in 627. Ashur-etel-ilani governed

in Assyria from about 633, but a general, Sin-shum-lisher,

soon rebelled against him and proclaimed himself counter-king. Some years

later (629?) Sin-shar-ishkun finally succeeded in

obtaining the kingship. In Babylonian documents dates can

be found for all three kings. To add to the confusion, until 626 there are

also dates of Ashurbanipal and a king named

Kandalanu. In 626 the Chaldean Nabopolassar (Nabu-apal-usur)

revolted from Uruk and occupied Babylon.

There were several changes in government. King Ashur-etel-ilani

was forced to withdraw to the west, where he died sometime after 625.

About the year 626 the Scythians laid

waste to Syria and Palestine. In 625 the

Medes became united under Cyaxares and

began to conquer the Iranian provinces of Assyria.

One chronicle relates of wars between Sin-shar-ishkun and

Nabopolassar in Babylonia in 625-623. It

was not long until the Assyrians were driven out of

Babylonia. In 616 the Medes struck

against Nineveh, but, according to the Greek

historian Herodotus, were driven back by the

Scythians. In 615, however, the Medes conquered

Arrapkha (Kirkuk), and in 614 they took

the old capital of Ashur, looting and destroying the

city. Now Cyaxares and Nabopolassar made

an alliance for the purpose of dividing Assyria. In 612

Kalakh and Nineveh succumbed to the

superior strength of the allies. The revenge taken on the

Assyrians was terrible: 200 years later Xenophon

found the country still sparsely populated.

Sin-shar-ishkun, king of

Assyria, found death in his burning palace. The commander of the

Assyrian army in the west crowned himself king in the

city of Harran, assuming the name of the founder of the

empire, Ashur-uballit II (611-609 BC).

Ashur-uballit had to face both the Babylonians

and the Medes. They conquered Harran in

610, without, however, destroying the city completely. In 609 the

remaining Assyrian troops had to capitulate. With this

event Assyria disappeared from history. The great empires

that succeeded it learned a great deal from the Assyrians,

both in the arts and in the organization

of their states.

Visit photo

gallery, for further related images