Demographic trends

(Social systems)

The impact of Western penetration on the indigenous

social and demographic structure in the nineteenth century was profound.

Western influence took the initial form of transportation and trading

links and the switch from tribal-based subsistence agriculture to cash

crop production--mostly dates--for export. As this process accelerated,

the nomadic population decreased both relatively and in absolute numbers

and the rural sedentary population increased substantially, particularly

in the southern region. This was accompanied by a pronounced

transformation of tenurial relations: the tribal, communal character of

subsistence production was transformed on a large scale into a

landlord-tenant relationship; tribal shaykhs, urban merchants, and

government officials took title under the open-ended terms of the newly

promulgated Ottoman land codes. Incentives and pressures on this emerging

landlord class to increase production (and thus exports and earnings)

resulted in expanded cultivation, which brought more and more land under

cultivation and simultaneously absorbed the "surplus" labor represented by

the tribal, pastoral, and nomadic character of much of Iraqi society. This

prolonged process of sedentarization was disrupted by the dismemberment of

the Ottoman Empire during and after World War I, but it resumed with

renewed intensity in the British Mandate period, when the political

structure of independent Iraq was formed.

This threefold transformation of rural

society--pastoral to agricultural, subsistence to commercial,

tribal-communal to landlord-peasant--was accompanied by important shifts

in urban society as well. There was a general increase in the number and

size of marketing towns and their populations; but the destruction of

handicraft industries, especially in Baghdad, by the import of cheap

manufactured goods from the West, led to an absolute decline in the

population of urban centers. It also indelibly stamped the subsequent

urban growth with a mercantile and bureaucratic-administrative character

that is still a strong feature of Iraqi society.

Thus, the general outline and history of Iraqi

population dynamics in the modern era can be divided into a period

extending from the middle of the nineteenth century to World War II,

characterized chiefly by urbanization, with a steady and growing movement

of people from the rural (especially southern) region to the urban

(especially central) region. Furthermore, the basic trends of the 1980s

are rooted in the particularly exploitive character of agricultural

practices regarding both the land itself and the people who work it.

Declining productivity of the land, stemming from the failure to develop

drainage along the irrigation facilities and the wretched condition of the

producers, has resulted in a potentially harmful demographic

trajectory--the depopulation of the countryside--that in the late 1980s

continued to bedevil government efforts to reverse the decades-long

pattern of declining productivity in the agricultural sector.

The accelerated urbanization process since World War II

is starkly illustrated in the shrinking proportion of the population

living in rural areas: 61 percent in 1947, followed by 56 percent in 1965,

then 36 percent in 1977, and an estimated 32 percent in 1987; concurrently

between 1977 and 1987 the urban population rose from 7,646,054 to an

estimated 11,078,000. The rural exodus has been most severe in Al Basrah

and Al Qadisiyah governorates. The proportion of rural to urban population

was lowest in the governorates of Al Basrah (37 percent in 1965, and 1

percent in 1987) and Baghdad (48 percent in 1965 and 19 percent in 1987).

It was highest in Dhi Qar Governorate where it averaged 50 percent in

1987, followed closely by Al Muthanna and Diyala governorates with rural

populations of 48 percent. Between 1957 and 1967, the population of

Baghdad and Al Basrah governorates grew by 73 percent and 41 percent

respectively. During the same years the city of Baghdad grew by 87 percent

and the city of Basra by 64 percent.

Because of the war, the growth of Al Basrah Governorate

has been reversed while that of Baghdad Governorate has accelerated

alarmingly, with the 1987 census figure for urban Baghdad being 3,845,000.

Iranian forces have mounted an offensive each year of the war since 1980,

except for early 1988, seeking to capture Basra and the adjoining area and

subjecting the city to regular bombardment. As a result, large numbers of

the population fled northward from Basra and other southern areas, with

many entering Baghdad, which was already experiencing overcrowding. The

government has attempted to deal with this situation by moving war

refugees out of the capital and resettling them in other smaller cities in

the south, out of the range of the fighting.

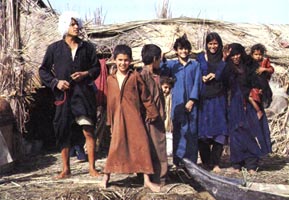

Rural Society

Rural Iraq contains aspects of the largely tribal mode

of social organization that prevailed over the centuries and still

survived in the 1980s--particularly in the more isolated rural areas, such

as the rugged tableland of the northwest and the marshes in the south. The

tribal mode probably originated in the unstable social conditions that

resulted from the protracted decline of the Abbasid Caliphate and the

subsequent cycles of invasion and devastation.

In the absence of a strong central authority and the

urban society of a great civilization, society developed into smaller units

under conditions that placed increasing stress on prowess, decisiveness,

and mobility. Under these conditions, the tribal shaykhs emerged as a

warrior class, and this process facilitated the ascendancy of the

fighter-nomad over the cultivator.

The gradual sedentarization that began in the

mid-nineteenth century brought with it an erosion of shaykhly power and a

disintegration of the tribal system. Under the British Mandate, and the

monarchy that was its creation, a reversal took place. Despite the

continued decline of the tribe as a viable and organic social entity, the

enfeebled power of the shaykhs was restored and enhanced by the British.

This was done to develop a local ruling class that could maintain security

in the countryside and otherwise head off political challenges to British

access to Iraq's mineral and agricultural resources and Britain's

paramount role in the Persian Gulf shaykhdoms. Through the specific

implementation of land registration, the traditional pattern of communal

cultivation and pasturage--with mutual rights and duties between shaykhs

and tribesmen--was superseded in some tribal areas by the institution of

private property and the expropriation by the shaykhs of tribal lands as

private estates. The status of the tribesmen was in many instances

drastically reduced to that of sharecroppers and laborers. The additional

ascription of judicial and police powers to the shaykh and his retinue

left the tribesmen-cum-peasants as virtual serfs, continuously in debt and

in servitude to the shaykh turned landlord and master. The social basis

for shaykhly power had been transformed from military valor and moral

rectitude to an effective possession of wealth as embodied in vast

landholdings and a claim to the greater share of the peasants' production.

This was the social dimension of the transformation

from a subsistence, pastoral economy to an agricultural economy linked to

the world market. It was, of course, an immensely complicated process, and

conditions varied in different parts of the country. The main impact was

in the southern half--the reverie economy-- more than in the sparsely

populated, rain-fed northern area. A more elaborate analysis of this

process would have to look specifically at the differences between Kurdish

and Arab shaykhs, between political and religious leadership functions,

between Sunni and Shia shaykhs, and between nomadic and reverie shaykhs,

all within their ecological settings. In general the biggest estates

developed in areas restored to cultivation through dam construction and

pump irrigation after World War I. The most autocratic examples of

shaykhly power were in the rice-growing region near Al Amarah, where the

need for organized and supervised labor and the rigorous requirements of

rice cultivation generated the most oppressive conditions.

The role of the tribe as the chief politico-military

unit was already well eroded by the time the monarchy was overthrown in

July 1958. The role of some tribal shaykhs had been abolished by the

central government. The tribal system survived longest in the

mid-Euphrates area, where many tribesmen had managed to register small

plots in their names and had not become mere tenants of the shaykh. In

such settings an interesting amalgam occurred of traditional tribal

customs and the newer influences represented by the civil servants sent to

rural regions by the central government, together with the expanded

government educational system. For example, the government engineer

responsible for the water distribution system, although technically not a

major administrator, in practice became the leading figure in rural areas.

He would set forth requirements for the cleaning and maintenance of the

canals, and the tribal shaykh would see to it that the necessary manpower

was provided. This service in the minds of tribesmen replaced the old

customary obligation of military service that they owed the shaykh and was

not unduly onerous. It could readily be combined with work on their own

grazing or producing lands and benefited the tribe as a whole. The

government administrators usually avoided becoming involved in legal

disputes that might result from water rights, leaving the disputes to be

settled by the shaykh in accordance with traditional tribal practices.

Thus, despite occasional tensions in such relationships, the power of the

central government gradually expanded into regions where Baghdad's

influence had previously been slight or absent.

Despite the erosion of the historic purposes of tribal

organization, the prolonged absence of alternative social links has helped

to preserve the tribal character of individual and group relations. The

complexity of these relations is impressive. Even in the southern,

irrigated part of the country there are notable differences between the

tribes along the Tigris, subject to Iranian influences, and those of the

Euphrates, whose historic links are with the Arab Bedouin tribes of the

desert. Since virtually no ethnographic studies on the Tigris peoples

existed in the late 1980s, the following is based chiefly on research in

the Euphrates region.

The tribe represents a concentric social system linked

to the classical nomadic structure but modified by the sedentary

environment and limited territory characteristic of the modern era. The

primary unit within the tribe is the named agnatic lineage several

generations deep to which each member belongs. This kinship unit shares

responsibilities in feuds and war, restricts and controls marriage within

itself, and jointly occupies a specified share of tribal land. The

requirements of mutual assistance preclude any significant economic

differentiation, and authority is shared among the older men. The primary

family unit rests within the clan, composed of two or more lineage groups

related by descent or adoption. Nevertheless, a clan can switch its

allegiance from its ancestral tribal unit to a stronger, ascendant tribe.

The clans are units of solidarity in disputes with other clans in the

tribe, although there may be intense feuding among the lineage groups

within the clan. The clan also represents a shared territorial interest,

as the land belonging to the component lineage groups customarily is

adjacent.

Several clans united under a single shaykh form a tribe

(ashira). This traditionally has been the dominant

politico-military unit although, because of unsettled conditions, tribes

frequently band together in confederations under a paramount shaykh. The

degree of hierarchy and centralization operative in a given tribe seems to

correlate with the length of time it has been sedentary: the Bani Isad,

for example, which has been settled for several centuries, is much more

centralized than the Ash Shabana, which has been sedentary only since the

end of the nineteenth century.

In the south, only the small hamlets scattered

throughout the cultivated area are inhabited solely by tribesmen. The most

widely spread social unit is the village, and most villages have resident

tradesmen (ahl as suq--people of the market)

and government employees. The lines between these village dwellers and the

tribe's people, at least until just before the war, were quite distinct,

although the degree varies from place to place. As the provision of

education, health, and other social services to the generally impoverished

rural areas increases, the number and the social influence of these non

tribal people increase. Representatives of the central government take

over roles previously filled by the shaykh or his representatives. A

government school competes with the religious school. The role of the

merchants as middlemen--buyers of the peasants' produce and providers of

seeds and implements as well as of food and clothing--has not yet been

superseded in most areas by the government-sponsored cooperatives and

extension agencies. Increasingly in the 1980s, government employees were

of local or at least rural origin, whereas in the 1950s they usually were

Baghdadis who had no kinship ties in the region, wore Western clothing,

and took their assignments as exile and punishment. In part the

administrators provoked the mutual antagonism that flourished between them

and the peasants, particularly as Sunni officials were often assigned to

Shia villages. The merchants, however, were from the region--if not from

the same village--and were usually the sons of merchants.

Despite some commercial developments in rural areas, in

the late 1980s the economic base was still agriculture and, to a lesser

but increasing extent, animal husbandry. Failure to resolve the technical

problem of irrigation drainage contributed to declining rural

productivity, however, and accentuated the economic as well as the

political role of the central government. The growth of villages into

towns and whatever signs of recent prosperity there were should be viewed,

therefore, more as the result of greater government presence than as

locally developed economic viability. The increased number of government

representatives and employees added to the market for local produce and,

more important, promoted the diffusion of state revenues into impoverished

rural areas through infrastructure and service projects. Much remained to

be done to supply utilities to rural inhabitants; just before the war, the

government announced a campaign to provide such essentials as electricity

and clean water to the villages, most of which still lacked these. The

government has followed through on several of these projects--particularly

in the south--despite the hardships caused by the war. The regime

apparently felt the need to reward the southerners, who had suffered

inordinately in the struggle.

Impact of Agrarian Reform

One of the most significant achievements of the

fundamentally urban-based revolutionary regime of Abd al Karim Qasim

(1958-63) was the proclamation and partial implementation of a radical

agrarian reform program. The scope of the program and the drastic shortage

of an administrative cadre to implement it, coupled with political

struggles within the Qasim regime and its successors, limited the

immediate impact of the program to the expropriation stage. The largest

estates were easily confiscated, but distribution lagged owing to

administrative problems and the wasted, saline character of much of the

land expropriated. Moreover, landlords could choose the best of the lands

to keep for themselves.

The impact of the reforms on the lives of the rural

masses can only be surmised on the basis of uncertain official statistics

and rare observations and reports by outsiders, such as officials of the

United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). The development of

cooperatives, especially in their capacity as marketing agents, was one of

the most obvious failures of the program, although isolated instances of

success did emerge. In some of these instances, traditional elders were

mobilized to serve as cooperative directors, and former sirkals,

clan leaders who functioned as foremen for the shaykhs, could bring a

working knowledge of local irrigation needs and practices to the

cooperative.

The continued impoverishment of the rural masses was

evident, however, in the tremendous migration that continued through the

1960s, 1970s, and into the 1980s from rural to urban areas. According to

the Ministry of Planning, the average rate of internal migration from the

countryside increased from 19,600 a year in the mid-1950s to 40,000 a year

in the 1958 to 1962 period. A study of 110 villages in the Nineveh and

Babylon governorates concluded that depressed rural conditions and other

variables--rather than job opportunities in the modern sector-- accounted

for most of the migration.

There was little doubt that this massive migration and

the land reform reduced the number of landless peasants. The most recent

comprehensive tenurial statistics available before the war broke out--the

Agricultural Census of 1971--put the total farmland (probably meaning

cultivable land, rather than land under cultivation) at over 5.7 million

hectares, of which more than 98.2 percent was held by "civil persons."

About 30 percent of this had been distributed under the agrarian reform.

The average size of the holdings was about 9.7 hectares; but 60 percent of

the holdings were smaller than 7.5 hectares, accounting for less than 14

percent of the total area. At the other end of the scale, 0.2 percent of

the holdings were 250 hectares or larger, amounting to more than 14

percent of the total. Fifty-two percent of the total was owner-operated,

41 percent was farmed under rental agreements, 4.8 percent was worked by

squatters, and only 0.6 percent was sharecropped. The status of the

remaining 1.6 percent was uncertain. On the basis of limited statistics

released by the government in 1985, the amount of land distributed since

the inception of the reform program totaled 2,271,250 hectares.

Political instability throughout the 1960s hindered

the implementation of the agrarian reform program, but after seizing power

in 1968 the Ba'ath regime made a considerable effort to reactivate it. Law

117 (1970) further limited the maximum size of holdings, eliminated

compensation to the landowner, and abolished payments by beneficiaries,

thus acknowledging the extremity of peasant indebtedness and poverty.

The reform created a large number of small holdings.

Given the experience of similar efforts in other countries, foreign

observers surmised that a new stratification has emerged in the

countryside, characterized by the rise of middle-level peasants who,

directly or through their leadership in the cooperatives, control much of

the agricultural machinery and its use. Membership in the ruling Ba'ath

Party is an additional means of securing access to and control over such

resources. Prior to the war, the party seemed to have few roots in the

countryside, but after the ascent of Saddam Husayn to the presidency in

1979 a determined effort was made to build bridges between the party cadre

in the capital and the provinces. It is noteworthy that practically all

party officials promoted to the second echelon of leadership at the 1982

party congress had distinguished themselves by mobilizing party support in

the provinces.

Even before the war, migration posed a serious threat

of labor shortages. In the 1980s, with the war driving whole communities

to seek refuge in the capital, this shortage has been exacerbated and was

particularly serious in areas intensively employing mechanized

agricultural methods. The government has attempted to compensate for this

shortage by importing turnkey projects with foreign professionals. But in

the Kurdish areas of the north--and to a degree in the southern region

infested by deserters--the safety of foreign personnel was difficult to

guarantee; therefore many projects have had to be temporarily abandoned.

Another government strategy for coping with the labor shortage caused by

the war has been to import Egyptian workers. It has been estimated that as

many as 1.5 million Egyptians have found employment in Iraq since the war

began.

Urban Society

Iraq's society just before the outbreak of the war was

undergoing profound and rapid social change that had a definite urban

focus. The city has historically played an important economic and

political role in the life of Middle Eastern societies, and this was

certainly true in the territory that is present-day Iraq. Trade and

commerce, handicrafts and small manufactures, and administrative and

cultural activities have traditionally been central to the economy and the

society, notwithstanding the overwhelming rural character of most of the

population. In the modern era, as the country witnessed a growing

involvement with the world market and particularly the commercial and

administrative sectors, the growth of a few urban centers, notably Baghdad

and Basra, has been astounding. The war, however, has altered this pattern

of growth remarkably--in the case of Baghdad accelerating it; in the case

of Basra shrinking it considerably.

Demographic estimates based on the 1987 census

reflected an increase in the urban population from 5,452,000 in 1970 to

7,646,054 in 1977, and to 11,078,000 in 1987 or 68 percent of the

population. Census data show the remarkable growth of Baghdad in

particular, from just over 500,000 in 1947 to 1,745,000 in 1965; and from

3,226,000 in 1977 to 3,845,000 in 1987.

The population of other major cities according to the

1977 census was 1,540,000 for Basra, 1,220,000 for Mosul, and 535,000 for

Kirkuk (detailed information from the October 1987 census was lacking in

early 1988). The port of Basra presents a more complex picture:

accelerated growth up to the time the war erupted, then a sharp

deceleration once the war started when the effects of the fighting around

the city began to be felt. Between 1957 and 1965, Basra actually had a

higher growth rate than Baghdad--90 percent in Basra as compared with

Baghdad's 65 percent. But once the Iranians managed to sink several

tankers in the Shatt al Arab, this effectively blocked the waterway and

the economy of the port city began to deteriorate. By 1988 repeated

attempts by Iran to capture Basra had further eroded the strength of the

city's commercial sector, and the heavy bombardment had rendered some

quarters of Basra virtually uninhabitable. Because of the war reliable

statistics were unavailable, but the city's population in early 1988 was

probably less than half that in 1977.

In the extreme north, the picture was somewhat

different. There, a number of middle-sized towns have experienced very

rapid growth--triggered by the unsettled conditions in the region. Early

in the war the government determined to fight Kurdish- guerrilla activity

by targeting the communities that allegedly sustained the rebels. It

therefore cleared whole tracts of the mountainous region of local

inhabitants. The residents of the cleared areas fled to regional urban

centers like Irbil, As Sulaymaniyah, and Dahuk; by and large they did not

transfer to the major urban centers such as Mosul and Kirkuk.

Statistical details of the impact of these population

shifts on the physical and spatial character of the cities were generally

lacking in the 1980s. According to accounts by on-the- spot observers, in

Baghdad--and presumably in the other cities as well--there appeared to

have been no systematic planning to cope with the growth of slum areas.

Expansion in the capital until the mid-1970s had been quite haphazard. As

a result, there were many open spaces between buildings and quarters.

Thus, the squatter settlements that mushroomed in those years were not

confined to the city's fringes. By the late 1950s, the sarifahs

(reed and mud huts) in Baghdad were estimated to number 44,000, or almost

45 percent of the total number of houses in the capital.

These slums became a special target of Qasim's

government. Efforts were directed at improving the housing and living

conditions of the sarifah dwellers. Between 1961 and 1963, many

of these settlements were eliminated and their inhabitants moved to two

large housing projects on the edge of the city-- Madinat ath Thawra and An

Nur. Schools and markets were also built, and sanitary services were

provided. In time, however, Ath Thawra and An Nur, too, became

dilapidated, and just before the war Saddam Husayn ordered Ath Thawra

rebuilt as Saddam City. This new area of low houses and wide streets has

radically improved the lifestyles of the residents, the overwhelming

majority of whom were Shias who had migrated from the south.

Another striking feature of the initial waves of

migration to Baghdad and other urban centers is that the migrants have

tended to stay, bringing with them whole families. The majority of

migrants were peasant cultivators, but shopkeepers, petty traders, and

small craftsmen came as well. Contact with the point of rural origin was

not totally severed, and return visits were fairly common, but reverse

migration was extremely rare. At least initially, there was a pronounced

tendency for migrants from the same village to relocate in clusters to

ease the difficulties of transition and maintain traditional patterns of

mutual assistance. Whether this pattern has continued into the war years

was not known, but it seems likely. A number of observers have reported

neighborhoods in the capital formed on the basis of rural or even tribal

origin.

The urban social structure has evolved gradually over

the years. In pre-revolutionary Iraq it was dominated by a well- defined

ruling class, concentrated in Baghdad. This was an internally cohesive

group, distinguished from the rest of the population by its considerable

wealth and political power. The economic base of this class was landed

wealth, but during the decades of the British Mandate and the monarchy, as

landlords acquired commercial interests and merchants and government

officials acquired real estate, a considerable intertwining of families

and interests occurred. The result was that the Iraqi ruling class could

not be easily separated into constituent parts: the largest commercial

trading houses were controlled by families owning vast estates; the

landowners were mostly tribal shaykhs but included many urban notables,

government ministers, and civil servants. Moreover, the landowning class

controlled the parliament, which tended to function in the most narrowly

conceived interest of these landlords.

There was a small but growing middle class in the 1950s

and 1960s that included a traditional core of merchants, shopkeepers,

craftsmen, professionals, and government officials, their numbers

augmented increasingly by graduates from the school system. The Ministry

of Education had been the one area during the monarchy that was relatively

independent of British advisers, and thus it was expanded as a conspicuous

manifestation of government response to popular demand. It was completely

oriented toward white-collar, middle-class occupations. Within this middle

class, and closely connected to the commercial sector, was a small

industrial bourgeoisie whose interests were not completely identical with

those of the more traditional sector.

Iraq's class structure at mid-century was characterized

by great instability. In addition to the profound changes occurring in the

countryside, there was the economic and social disruption of shortages and

spiraling inflation brought on by World War II. Fortunes were made by a

few, but for most there was deprivation and, as a consequence, great

social unrest. Longtime Western observers compared the situation of the

urban masses unfavorably with conditions in the last years of Ottoman

rule. An instance of the abrupt population shifts was the Iraqi Jews. The

establishment of the state of Israel led to the mass exodus of this

community in 1950, to be replaced by Shia merchants and traders, many of

whom were descendants of Iranian immigrants from the heavily Shia

populated areas of the south.

The trend of urban growth, which had commenced in the

days immediately preceding the revolution, took off in the mid-1970s, when

the effects of the sharp increases in the world price of oil began to be

felt. Oil revenues poured into the cities where they were invested in

construction and real estate speculation. The dissatisfied peasantry then

found even more cause to move to the cities because jobs--mainly in

construction--were available, and even part-time, unskilled labor was an

improvement over conditions in the countryside.

As for the elite, the oil boom of the 1970s brought

greater diversification of wealth, with some going to those attached to

the land, and some to those involved in the regime, commerce, and,

increasingly, manufacturing. The working class grew but was largely

fragmented. A relatively small number were employed in businesses of ten

or more workers, whereas a much larger number were classified as wage

workers, including those in the services sector. Between the elite and the

working masses was the lower middle class of petty bourgeoisie. This

traditional component consisted of the thousands of small handicraft

shops, which made up a huge part of the so-called manufacturing sector,

and the even more numerous one-man stores. The newer and more rapidly

expanding part of this class consisted of professionals and

semiprofessionals employed in services and the public sector, including

the officer corps, and the thousands of students looking for jobs. This

class became particularly significant in the 1980s because former members

of it have become the nation's elite. Perhaps the most important aspect of

the growth of the public sector was the expansion of educational

facilities, with consequent pressures to find white-collar jobs for

graduates in the non commodity sectors.

Stratification and Social Classes

The pre-revolutionary political system, with its

parliament of landlords and hand-picked government supporters, was

increasingly incompatible with the changing social reality marked by the

quickening pace of urban-based economic activity fueled by the oil

revenues. The faction of the elite investing in manufacturing, the petty

bourgeoisie, and the working classes pressured the state to represent

their interests. As the armed forces came to reflect this shifting balance

of social forces, a radical political change became inevitable. The social

origins and political inclinations of the ”Free officers” who carried out

the 1958 overthrow of the monarchy and the various ideological parties

that supported and succeeded them clearly reflect the middle-class

character of the Iraqi Revolution. Both the agrarian reform program and

the protracted campaign against the foreign oil monopoly were aimed at

restructuring political and economic power in favor of the urban based

middle and lower classes. The political struggle between the self-styled

radicals and moderates in the 1960s mainly concerned the role of the state

and the public sector in the economy: the radicals promoted a larger role

for the state, and the moderates wanted to restrict it to the provision of

basic services and physical infrastructure.

There was a shift in the distribution of income after

1958 at the expense of the large landowners and businessmen and in favor

of the salaried middle class and, to a lesser degree, the wage earners and

small farmers. The Ba'ath Party, in power since July 1968, represented the

lower stratum of the middle class: sons of small shopkeepers, petty

officials, and graduates of training schools, law schools, and military

academies. In the 1980s, the ruling class tended to be composed of high

and middle echelon bureaucrats who either had risen through the ranks of

the party or had been co-opted into the party because of their technical

competence, i.e., technocrats. The elite also consisted of army officers,

whose wartime loyalty the government has striven to retain by dispensing

material rewards and gifts.

The government's

practice of lavishing rewards on the military has also affected the lower

classes. Martyrs' benefits under the Ba'ath have been extremely generous.

Thus, the families of youths killed in battle could expect to receive at

least an automobile and more likely a generous pension for life.