New Page 1

New Page 1

|

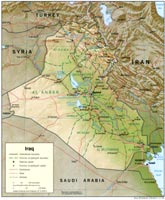

Relief

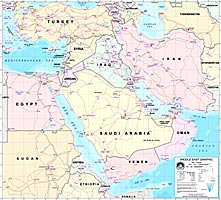

Iraq is uniquely positioned at the

heart of the Middle East, between latitudes 2927' and 3723' North and

longitudes 3842' and 4823' East. It is bounded by Iran in the east, Turkey

in the north, Syria in the northwest, Jordan and Saudi Arabia in the west

and southwest, and Kuwait and the Gulf in the south. The country's

greatest axis, running in a north-northwest to south-southeast direction

from the Turkish border to the shores of the Gulf, is almost 1,000 km.

Iraq is traversed by two great

rivers, the Tigris and the Euphrates, both of which rise in the eastern

mountains of Turkey and enter Iraq along its northwestern borders. After

flowing for some 1,200 km through Iraq, these two rivers converge at

Karmat Al, just north of Basrah, to form the tidal Shatt Al Arab waterway,

which flows some 110 km to enter the Gulf. The Euphrates does not receive

any tributaries within Iraq, while the Tigris receives four main

tributaries, the Khabour, Great Zab, Little Zab and Diyala, which rise in

the mountains of eastern Turkey and northwestern Iran and flow in a

southwesterly direction until they meet the Tigris River. A seasonal

river, Al Authaim, rising in the highlands of northern Iraq also flows

into the Tigris, and is the only significant tributary arising entirely

within Iraq.

Most geographers, including those of the Iraqi government, discuss the

country's geography in terms of four main zones or regions: the highlands

“mountain region” in the north and northeast; the upper plains and

foothills region, or the rolling upland between the upper Tigris and

Euphrates rivers (in Arabic the Dijla and Furat, respectively); the

alluvial plain through which the Tigris and Euphrates flow; and the desert

in the west and southwest. Iraq's official statistical reports give the

total land area as 438,446 square kilometers, whereas a United States

Department of State publication gives the area as 434,934 square

kilometers.

The mountain region

This extends from the northern and northeastern frontiers of Iraq on the

borders of Turkey and Iran south to a line from Sinjar in Mosul Province

to Zakho, Dohuk, Arbil, Kirkuk, Tuz, Kifri and finally Halabja on the

Iranian border. Heights range from 900 to 3,660 m.

The upper plains and foothills

region

This steppic sub-mountain belt extends from the high mountains to the

foot of Jabal Hemrin, and forms a transitional area between the highland

areas and the desert plains.

The desert plateau region

The desert plateau comprises the largest part of Iraq (almost 57% of the

total land area), and extends from the edge of the upper plains and

banks of the Euphrates River to the frontiers with Syria, Jordan and

Saudi Arabia. Conditions grade from semi-desert (the upper Jazirah,

especially the area between the Tigris and Euphrates below Jabal Hemrin)

to a more typical sandy desert in the far south and west.

The lower valley

The great alluvial plains of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers comprise

about 25% of Iraq's surface area. Topographically, this region is

composed of marshlands and low-lying plains dissected by sluggish

drainage channels. The whole area is extremely flat, with a fall of only

4 cm/km over the last 300 km of the Euphrates and 8 cm/km along the

Tigris. Thus, the annual flooding, which may be in the order of 1.5 to 3

meters, regularly inundates immense areas of land (the highest flood

ever recorded was 9 meters on the Tigris in 1954). As a result, much of

the region is swampy. At the height of the flood season in spring,

virtually all of the land in the triangle Basrah-Amara-Nasiriya was

formerly one expanse of continuous marshland, while in the dry season

there remained numerous large permanent lakes and extensive reed beds

inter-connected by an intricate network of channels. In recent years,

the seasonal flooding has occurred on a much smaller scale than before

because of intensive water regulation by dams upstream on the Tigris and

Euphrates and especially on the Euphrates in Turkey and Syria.

The desert zone, an area lying west and southwest of the Euphrates River,

is a part of the Syrian Desert, which covers sections of Syria, Jordan,

and Saudi Arabia. The region, sparsely inhabited by pastoral nomads,

consists of a wide, stony plain interspersed with rare sandy stretches. A

widely ramified pattern of wadis--watercourses that are dry most of the

year--runs from the border to the Euphrates. Some Wadis are over 400

kilometers long and carry brief but torrential floods during the winter

rains.

The uplands region, between the Tigris north of Samarra and the Euphrates

north of Hit, is known as Al Jazirah (the island) and is part of a larger

area that extends westward into Syria between the two rivers and into

Turkey. Water in the area flows in deeply cut valleys, and irrigation is

much more difficult than it is in the lower plain. Much of this zone may

be classified as desert.

The northeastern highlands begin just south of a line drawn from Mosul to

Kirkuk and extend to the borders with Turkey and Iran. High ground,

separated by broad, undulating steppes, gives way to mountains ranging

from 1,000 to nearly 4,000 meters near the Iranian and Turkish borders.

Except for a few valleys, the mountain area proper is suitable only for

grazing in the foothills and steppes; adequate soil and rainfall, however,

make cultivation possible. Here, too, are the great oil fields near Mosul

and Kirkuk. The northeast is the homeland of most Iraqi Kurds.

The alluvial plain begins north of Baghdad and extends to the Persian

Gulf. Here the Tigris and Euphrates rivers lie above the level of the

plain in many places, and the whole area is a delta interlaced by the

channels of the two rivers and by irrigation canals. Intermittent lakes,

fed by the rivers in flood, also characterize southeastern Iraq. A fairly

large area (15,000 square kilometers) just above the confluence of the two

rivers at Al Qurnah and extending east of the Tigris beyond the Iranian

border is marshland, known as Hawr al Hammar, the result of centuries of

flooding and inadequate drainage. Much of it is permanent marsh, but some

parts dry out in early winter, and other parts become marshland only in

years of great flood.

Because the waters of the Tigris and Euphrates above their confluence are

heavily silt laden, irrigation and fairly frequent flooding deposit large

quantities of salty loam in much of the delta area. Windborne silt

contributes to the total deposit of sediments. It has been estimated that

the delta plains are built up at the rate of nearly twenty centimeters in

a century. In some areas, major floods lead to the deposit in temporary

lakes of as much as thirty centimeters of mud.

The Tigris and Euphrates also carry large quantities of salts. These, too,

are spread on the land by sometimes excessive irrigation and flooding. A

high water table and poor surface and subsurface drainage tend to

concentrate the salts near the surface of the soil. In general, the

salinity of the soil increases from Baghdad south to the Persian Gulf and

severely limits productivity in the region south of Al Amarah. The

salinity is reflected in the large lake in central Iraq, southwest of

Baghdad, known as Bahr al Milh (Sea of Salt). There are two other major

lakes in the country to the north of Bahr al Milh: Buhayrat ath Tharthar

and Buhayrat al Habbaniyah.

The Euphrates originates in Turkey, is augmented by the Nahr (river) al

Khabur in Syria, and enters Iraq in the northwest. Here it is fed only by

the wadis of the western desert during the winter rains. It then winds

through a gorge, which varies from two to sixteen kilometers in width,

until it flows out on the plain at Ar Ramadi. Beyond there the Euphrates

continues to the Hindiyah Barrage, which was constructed in 1914 to divert

the river into the Hindiyah Channel; the present day Shatt al Hillah had

been the main channel of the Euphrates before 1914. Below Al Kifl, the

river follows two channels to As Samawah, where it reappears as a single

channel to join the Tigris at Al Qurnah.

The Tigris also rises in Turkey but is significantly augmented by several

rivers in Iraq, the most important of which are the Khabur, the Great Zab,

the Little Zab, and the Uzaym, all of which join the Tigris above Baghdad,

and the Diyala, which joins it about thirty-six kilometers below the city.

At the Kut Barrage much of the water is diverted into the Shatt al Gharraf,

which was once the main channel of the Tigris. Water from the Tigris thus

enters the Euphrates through the Shatt al Gharraf well above the

confluence of the two main channels at Al Qurnah.

Both the Tigris and the Euphrates break into a number of channels in the

marshland area, and the flow of the rivers is substantially reduced by the

time they come together at Al Qurnah. Moreover, the swamps act as silt

traps, and the Shatt al Arab is relatively silt free as it flows south.

Below Basra, however, the Karun River enters the Shatt al Arab from Iran,

carrying large quantities of silt that present a continuous dredging

problem in maintaining a channel for ocean-going vessels to reach the port

at Basra. This problem had been superseded by a greater obstacle to river

traffic, however, namely the presence of several sunken hulks that had

been rusting in the Shatt al Arab since early in the war.

The waters of the Tigris and Euphrates are essential to the life of the

country, but they may also threaten it. The rivers are at their lowest

level in September and October and at flood in March, April, and May when

they may carry forty times as much water as at low mark. Moreover, one

season's flood may be ten or more times as great as that in another year.

In 1954, for example, Baghdad was seriously threatened, and dikes

protecting it were nearly topped by the flooding Tigris. Since Syria built

a dam on the Euphrates, the flow of water has been considerably diminished

and flooding was no longer a problem in the mid-1980s. In 1988 Turkey was

also constructing a dam on the Euphrates that would further restrict the

water flow.

Until the mid-twentieth century, most efforts to control the waters were

primarily concerned with irrigation. Some attention was given to problems

of flood control and drainage before the revolution of July 14, 1958, but

development plans in the 1960s and 1970s were increasingly devoted to

these matters, as well as to irrigation projects on the upper reaches of

the Tigris and Euphrates and the tributaries of the Tigris in the

northeast. During the war, government officials stressed to foreign

visitors that, with the conclusion of a peace settlement, problems of

irrigation and flooding would receive top priority from the government.

Boundaries

The border with Iran has been a continuing source of conflict and was

partially responsible for the outbreak in 1980 of the present war. The

terms of a treaty negotiated in 1937 under British auspices provided that

in one area of the Shatt al Arab the boundary would be at the low water

mark on the Iranian side. Iran subsequently insisted that the 1937 treaty

was imposed on it by "British imperialist pressures," and that the proper

boundary throughout the Shatt was the thalweg. The matter came to a head

in 1969 when Iraq, in effect, told the Iranian government that the Shatt

was an integral part of Iraqi territory and that the waterway might be

closed to Iranian shipping.

Through Algerian mediation, Iran and Iraq agreed in March 1975 to

normalize their relations, and three months later they signed a treaty

known as the Algiers Accord. The document defined the common border all

along the Shatt estuary as the thalweg. To compensate Iraq for the loss of

what formerly had been regarded as its territory, pockets of territory

along the mountain border in the central sector of its common boundary

with Iran were assigned to it. Nonetheless, in September 1980 Iraq went to

war with Iran, citing among other complaints the fact that Iran had not

turned over to it the land specified in the Algiers Accord. This problem

has subsequently proved to be a stumbling block to a negotiated settlement

of the ongoing conflict.

In 1988 the boundary with Kuwait was another outstanding problem. It was

fixed in a 1913 treaty between the Ottoman Empire and British officials

acting on behalf of Kuwait's ruling family, which in 1899 had ceded

control over foreign affairs to Britain. The boundary was accepted by Iraq

when it became independent in 1932, but in the 1960s and again in the

mid-1970s, the Iraqi government advanced a claim to parts of Kuwait.

Kuwait made several representations to the Iraqis during the war to fix

the border once and for all but Baghdad has repeatedly demurred, claiming

that the issue is a potentially divisive one that could enflame

nationalist sentiment inside Iraq. Hence in 1988 it was likely that a

solution would have to wait until the war ended.

In 1922 British officials concluded the Treaty of Mohammara with Abd al

Aziz ibn Abd Al Rahman Al Saud, who in 1932 formed the Kingdom of Saudi

Arabia. The treaty provided the basic agreement for the boundary between

the eventually independent nations. Also in 1922 the two parties agreed to

the creation of the diamond-shaped Neutral Zone of approximately 7,500

square kilometers adjacent to the western tip of Kuwait in which neither

Iraq nor Saudi Arabia would build permanent dwellings or installations.

Bedouins from either country could utilize the limited water and seasonal

grazing resources of the zone. In April 1975, an agreement signed in

Baghdad fixed the borders of the countries. Despite a rumored agreement

providing for the formal division of the Iraq-Saudi Arabia Neutral Zone,

as of early 1988 such a document had not been published. Instead, Saudi

Arabia was continuing to control oil wells in the offshore Neutral Zone

and had been allocating proceeds from Neutral Zone oil sales to Iraq as a

war payment.

|